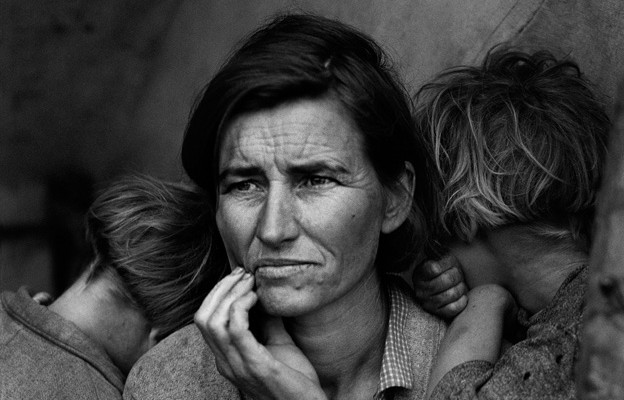

Photos do not hold the details of human experience intact. We do not know Aylan Kurdi’s life, all we know is his lifeless body. We can see his round cheeks resting in the sand, we can imagine the waves lapping at his tiny feet, yet we cannot know how he felt on his doomed journey. We are witnesses to a single moment. The photo is a brief window into a struggle we will never know. The victims of that struggle are, as Neville Chamberlain dismissively said of the Poles, people we do not know.

In other words, there is an inevitable distance between witness and victim. There is distance in experience, we as observers and Others as victims, and with that comes the distance in our ability to understand their pain. For that reason it seems rather voyeuristic for the well-meaning masses to co-opt the private tragedy of Aylan Kurdi’s death and transform it into a moment of public grief. This is not our struggle. Aylan was not our child. He did not die in order for us to have an emotional and political experience.

Yet that is exactly what is happening. As Jonathan Freedland notes, ‘that old Stalinist maxim about a million deaths being a statistic [and] a single death a tragedy’ applies. When we see Kurdi’s corpse we are not just witnessing the moment the authorities discover a dead child, we also detect the ghosts of our own guilt. We are forced to confront the knowledge that this is not the first child or the last child to die in a desperate struggle to reach us. We feel alienated from our reluctant governments – the same governments who helped create the disaster which millions of Syrians are fleeing from.

There is the risk that Kurdi’s death, and the photo that informed the world of it, degenerates into the temporary activism of Kony 2012 or #BringBackOurGirls. Earnest Westerners will share and comment, their proposed solutions will ask what is the need without examining the cause; they will centre themselves as (white) saviours. It all amounts to a brief indulgence in another people’s struggle and another person’s death. It could become a kind of virtue signal, a demonstration of how you are on the right side of tragedy.

But this characterisation does not only seem unfair, it is likely to prove inaccurate. Something is happening around this photo that did not happen around, say, the Kony 2012 film: activists are organising for concrete political change in their own countries (they are not retweeting for useless political intervention in other countries, as with Kony 2012). Even in New Zealand, a country as far removed from the chaos of Syria or the lethargy of Europe as one could imagine, activists are holding spontaneous demonstrations outside of Parliament – even local mayors are campaigning for a lift in the country’s refugee quota. Everyone is tweeting on #doublethequota.

It seems Kurdi’s photo has transcended the mere anthropological – it is more than just its subject and object – or media spectacle. It is more than front page fodder, and is becoming something intensely political. This politicisation in thought and feeling is helping shrink that inevitable gap between witnesses and victims. Susan Sontag knew that photos could become ‘totems of causes’ because ‘sentiment is more likely to crystallise around a photograph than around a verbal slogan,’ yet she still held that in front of an image of atrocity you are still often either in the position of spectator or of coward. But this time activists are beating Sontag’s ‘culture of spectatorship’ by organising around the photo.

This is easier said than done, of course, and it might sound like a glib and bureaucratic response to the scarcely imaginable human tragedy. But it is absolutely necessary. Without political organising it is too easy to fall back on the idea that disaster is unstoppable. We are bombarded with photos of tragedy and unrest every day; journalists chase calamities at the heels. In response we often switch off. Anger as a political emotion dissipates and is replaced by apathy. But political organising and the movements that grow around it guard against this individual exhaustion and moral resignation.

None of this is to say that photos necessarily mend our ignorance of the history and the social and economic causes of suffering. ‘To designate a hell’, explains Sontag, ‘is not [to] tell us anything about how to extract people from that hell’. Photos can show, but movements tell narratives to help us understand. As intrusive and gratuitous as it may be to bear witness to Kurdi’s death, it seems like a good in itself to have acknowledged the human suffering of the refugee crisis and then organise to repair it. This is better than indifference or ignorance, it is certainly better than seeing the photo for the sake of a temporary emotional and political experience.

Adam Smith, better known for his theory of the invisible hand, reminds us in The Theory of Moral Senses that it is sympathy which is the centre of social gravity. This seems like an elegant idea. Through photos we can sympathise with the historical horrors of Hiroshima, napalm in Vietnam, ethnic cleansing in the Balkans or famines in India and Africa. But the better centre of social gravity is collective empathy. Through it, we can all ask of Kurdi’s photo: who caused the suffering we see? Is it excusable? Was it inevitable? And is there some state of affairs which was once acceptable but which we now ought to challenge?