Recently, after a period of living in Europe, I returned to Australia. At the airport I fed my passport to the electronic control system, had my face scanned and was then confronted by a sign: ‘Please let authorities know if you would prefer not to be filmed by Channel Seven’s Border Security.’ Even though it was not the first time I had seen the sign, it felt surreal, and not just because I was jetlagged. With disbelief, I thought of this continent peopled with migrants, built on Indigenous dispossession, and yet so obsessed with policing its borders. A paradox? On the flight home, I’d had a brief conversation with an Australian woman sitting next to me, who had migrated to Australia from Sri Lanka twenty-eight years ago. During our discussion I had lamented Australia’s harsh treatment of refugees in detention centres. She shrugged and seemed to accept the need to ‘protect borders’.

For whom and from whom are borders being protected? At a conference of the Migration Policy Centre held at the European University Institute earlier this month, Special Policy Advisor to the Director General of the International Organisation for Migration Gervais Appave wondered why it is that in a world based on the exchange of capital, goods, services and communications (conditions which have given rise to increased human mobility), the migration of people is met with such awkwardness. For the exclusionary mechanisms made into spectacle by television programmes such as Border Security and enforced by Australian governments on both sides of the political spectrum, is it necessary to forget, or even cultivate an imposed amnesia, in order to go along with the violence the policing of borders demands?

In my academic work I have wondered about how particular media in Australia condone or even produce exclusion, and consequently, racism. Representations of Australia’s diversity in dominant media still limit the extent to which migrants are able to develop a sense of cultural belonging or citizenship in the country. Media engagement with racial and ethnic diversity tends to be insufficiently representative of lived realities. Meanwhile, depictions of migrants and refugees as outsiders in mainstream Australian media and political discourse reinforce an exclusive idea of who can be Australian. In the face of this, it is unsurprising that many would be in favour of reinforcing Australia’s borders. To counter these media tendencies, I found that image-making which reflects the complexities of what it means to be Australian and the nuances of belonging to country is critical.

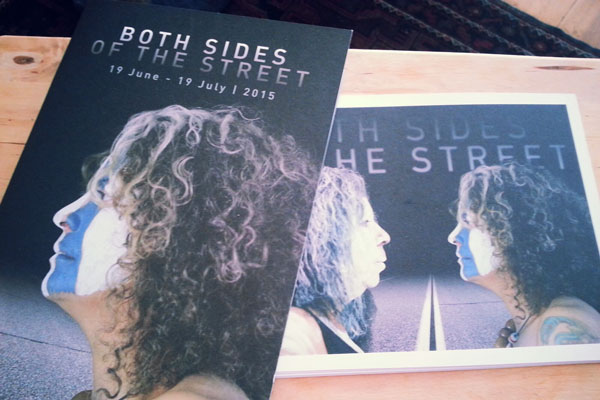

Art may create a space of home. I witnessed such art on display at the Counihan Gallery’s Both Sides of the Street, a landmark exhibition curated by Blak Dot Gallery Director Kimba Thompson and Eugenia Flynn. Setting the stage for a new era of mature debate about what it means to be Australian in the twenty-first century, Both Sides of the Street opened during Refugee Week, and was timed to celebrate NAIDOC Week. In the introduction of the catalogue to the exhibition, Assistant Curator Eugenia Flynn writes:

Both Sides of the Street redresses the historical past of keeping First Peoples and culturally and linguistically diverse communities apart. It asks artists and viewers to consider the work of solidarity and explore shared experiences, and what it means to live and make art on colonised land.

The exhibition draws together Indigenous Australian artists who have partnered with Australian artists from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Their collaborations map new registers of belonging that are capable of complicating and contesting national boundaries as they comprise multiple affiliations. Together, their artworks step away from caricatures and racism, opening up vital understandings of belonging to country. At the exhibition opening, Aboriginal activist Robbie Thorpe gave a speech addressing those seeking asylum in Australia. To reaffirm Indigenous sovereignty and offer welcome, Thorpe held up an Indigenous colour-themed Aboriginal Passport to Country.

What is perhaps most remarkable about the exhibition is the sense of cultural continuity that has developed between the artists through their collaborative works. Via exploration of a language of gesture, for example, Nadia Faragaab (of Somali background) and Vicki Couzens’ (Kirrae Wurrong and Gunditjmara) video work ‘Gestural Intent’ takes on a register of non-verbal dialogue to create spaces of non-fixity. The insights gained by Couzens and Faragaab about one another’s ‘worldview, culture and ways of thinking’ (the artists had assumed more difference than commonality at the outset of their artistic partnership):

led them to the conclusion that it [is] the mainstream, dominant culture that [is] on the ‘other side of the street’ and that they are on ‘the same side of the street’.

Set up side-by-side behind a white translucent curtain, screens with recordings on loop of each artist performing culturally specific gestures broaden the repertoire of human communication, engaging animal spirits, holding the immaterial in the material. Couzens, painted with circles and stripes, is filmed in a night landscape from up close while, in the background, she dances beside fire. Faragaab appears in shadow against a white backdrop. In some moments she can be observed in a jalbaabka (a burqa-like garment worn by Somali women since the civil war in Somalia). Faragaab deploys her body and its extremities to enact the rhythms and signs of Somali non-verbal language. At times the gestures of both artists reminded me of watching birds or snakes, leading me to imagine the artists’ shared language of gesture on display as one that disrupts anthropocentrism.

‘Fear and Loathing in L’Australie’ by Georgia MacGuire (Wurundjeri) and Gina Ropiha (Maori) responds to the traumas that are a legacy of colonialism. Finding ways to heal through listening are central to their artwork. Made from possum skin and nets woven from Ropiha’s own hair to express her grief, ‘fellowship and awful familiarity’ with MacGuire’s story, the artists have created an artwork of objects reminiscent, in their psychic and totemic potency, of the works of French-American artist Louise Bourgeois. The artists share a deep respect towards their ancestral traditions and sensitivity to the damage inflicted by colonialism upon human dignity.

Likewise, through the shared traditions of water and weaving in ‘Weaving the Landscape’, Treahna Hamm (Yorta Yorta) and Kirsten Lyttle (Maori) express solidarity with their ancestors. Hamm’s breastplate is presented as an ‘icon of present and future generations to walk together’. Lyttle photographed Melbourne’s Merri Creek and then wove the image using traditional Maori patterns, repeating ‘the same patterns and movements that my ancestor’s hands made.’

Texta Queen (Indian) partnered with Arika Roo Waulu (Gunnai) whose ‘Visa Pass’ installation is a video-projection onto bark. Known for her fibre-tip pen portraits such as the satirical mock-up cover of The Australian newspaper in which Texta Queen responds to the question ‘But where are you really from?’, in this exhibition her contribution ‘A Head’ is in the form of an aluminium coin on which the words ‘Seeking a Better Life On Your Land 1975’ are laser-etched to frame a self-portrait (a woman wearing a Texta headdress) in place of where we would ordinarily see a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II. The artists’ conversations about what it means to be a neocoloniser (that is, someone who has had their ancestral lands colonised and has sought a better life in a new context) led them to reinterpret ‘opposite sides of an Australian coin’s colonial figurehead/Indigenous fauna’. Waulu views her piece as ‘an example of what a visa for the neo-coloniser would look like,’ a concept that derives from the Aboriginal Passport pioneered by Robbie Thorpe.

At the centre of the main gallery space, Mutti Mutti Yorta Yorta artist Maree Clark and Somali-Australian artist Susan Maco Forrester bring together indigenous Somali and Australian cultures in their work titled ‘Sistas United in Sorrow’.

We are informed by country, the dome

Shapes that represents Kopis and caves

in this land and the art of ancestors

in rock shelters in Somaliland.

With their faces painted in ochre, the artists’ photographic portraits hang beside each other opening onto a semi-circle of soil that serves as a gathering place in which loss can be expressed and shared. A Kopi (widow’s) mourning cap is placed at the centre of the soil, covering a video installation that features the artists performing a smoking ceremony during which Forrester is wearing a traditional Somali guntiino. The ceremony imparts a trajectory of shared healing.

Simon Rose (Murri) and Dulcie Stewart’s (iTaukei) works focus on their relationship to land. A red serpent sits on shifting earth. It is the earth, rather than the serpent, that slithers, suggesting the continuity of indigenous cultures and the changes and destruction of the land wrought by colonialism. In the same room, Racquel Austin-Abdullah (Wangkumara and Pashtun) and Pacific artist Cecilia Kavara Verran’s ‘Not the Fantasy’ sand and light installation explores the act of drawing and engraving from a multimedia projection. At the exhibition opening, children were invited onto the sand to participate in the work, which remains contingent, mutable and responsive, yielding to the marks made on it.

‘Blue Vision’ by Peter Waples-Crowe (Wiradjuri), Jen Rae (Métis Alberta) and Jason Baerg (Cree Métis) is a collection of totemic found objects – all in arresting shades of blue – that are scattered in three separate locations of the gallery. Upon entering, emu heads of polystyrene foam lie next to a totem on which a plastic monkey mask and a dog mask are affixed. In another corner, a dog silhouette vomits the gewgaws of the Anthropocene skywards onto a wall. These drift like smoke until they assume the form of a flying bird. Across the room, synthetic bristle brushes sprout from tree branches and plastic poles, intimating the degree to which the petrochemical industry is now intertwined with the organically grown.

In a similar vein, Steven Rhall (Taungurung) and Siying Zhou’s (Chinese) ‘Feeling Invisible at the Dinner without Lamb’ juxtaposes remnants of excavated earth before a video projection of traffic on a busy city freeway. Each fragment of earth was once under the road and captures the light from the projection. Cars are driven across the land fragments, their homo oeconomicus drivers disconnected from their histories. The artists’ sense of ‘shared marginality’ motivated them to address the disjuncture imposed on the local earth by the non-places of contemporary globalised colonialism.

The artists in Both Sides of the Street draw together First Peoples’ cultural, linguistic and historical knowledge, complicating what it means to be Australian, and providing a counterpoint to amnesia and reductive stereotypes. Their collaborative mixed media works archive indigenous experiences of belonging and establish collective futures between global and local realities. By re-framing of Australianness in accordance with Indigenous epistemologies, human dignity in this country is given life rather than lie, making way for cultural, as much as official, citizenship.