The Independent newspaper recently reported that the British Broadcasting Corporation is designing a television program in which unemployed and low paid workers will compete against each other, The Hunger Games-style, for cash prizes. The idea follows the success of Benefits Street, a UK reality TV show similar to the much-criticised SBS series, Struggle Street, about an area in Birmingham where ninety per cent of the residents are on social welfare benefits.

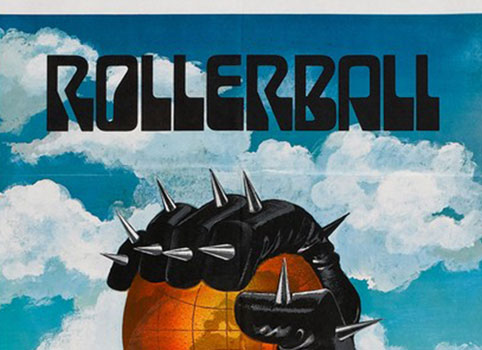

The newspaper report is one of several recent things that have got me thinking about how aspects of dystopian cinema are bleeding into real life. Another is the fortieth anniversary in late June of the science fiction film, Rollerball. Although derided by critics upon release for its violence, the film is now viewed as one of the high points of seventies dystopian cinema. It has also proven remarkably prescient regarding aspects of the future it depicted.

Rollerball is set in 2018. Nation-states no longer exist but are replaced by huge corporations, each focusing on an aspect of human need: transport, food, communication, housing, luxury, energy, etc. The most popular form of entertainment is a violent sport called Rollerball, and the most successful competitor is Jonathan E, who plays for Houston, the city controlled by the Energy Corporation.

Jonathan is summoned by a senior Energy Corporation executive and told that because he has reached the pinnacle of achievement in the game it’s time for him to resign. When Jonathan questions the directive, the executive replies: ‘Corporate society takes care of everything and all it asks of anyone – all it asks of anyone, ever – is not to interfere with management decisions.’ The corporations make the game more brutal to force Jonathon out, eventually making the players fight each other in matches where there are no rules.

Forty years on, the matches between the various corporate sponsored teams still look dynamic and visceral. Indeed, Rollerball was the first feature film to mention stunt professionals in its list of credits. Other aspects haven’t dated so well. The way the players dress – gridiron helmets, shoulder padding, spiked leather gloves and roller skates, the polyester jumpsuits they wear as casual clothes, the futuristic architecture – are a very seventies version of how we imagined the future would look.

The film’s version of capitalism – a series of well-functioning, neatly ordered monopolies – is nothing like the chaotic reality of the free market. Its depiction of gender relations is similarly anachronistic. Relations between men and women have been corporatized: women are assigned to men, and one of the reasons Jonathan E is so reticent to retire is the lack of anything else in his life since his long-time wife was reassigned to a senior executive.

In other ways, Rollerball was well and truly ahead of its time.

The film was based on the 1973 short story ‘Rollerball Murder’ by American novelist William Harrison, who also wrote the script for the movie. The short story concerned an athlete who has triumphed in the game of Rollerball, but starts to wonder whether there is more to life than adulation, sex, money and drugs. The athlete tries to educate himself about history, only to realise the government has destroyed it.

In the film version, Jonathan’s refusal to leave the game prompts him to investigate how the corporations came to rule the world. He goes to a library, to discover all books have been summarised in digital format. ‘Who summarises them?’ he asks the woman behind the desk, who is more a receptionist than librarian. ‘I suppose the computer summarises them,’ she says.

He travels to Geneva to consult Zero, a liquid core super computer that contains the knowledge of all the world’s books. An elderly technician, Zero’s keeper, greets Jonathan upon his arrival with the news only that morning the computer had lost all the files relating to the thirteenth century. ‘Not much of a century,’ the scientist says glumly. ‘Just Dante and a few corrupt Popes.’ The computer answers questions about the corporations with meaningless jargon and tautologies and Jonathan walks away none the wiser.

The idea so much data could be stored on a computer must have seemed fantastic in 1975. That so much data could be lost, until recently, also seemed the stuff of fiction. But in a conference address in February this year, Google’s Vice President, Vint Cerf, warned we face the threat of ‘forgotten generations or even a forgotten century’ though what he referred to as ‘bit rot’, the process by which old computer files became useless, and because the hardware needed to make sense of the files no longer exists anywhere except in a museum.

Dystopia has been a key subject of film right back to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in 1927, and the specific dystopias have always mirrored the dominant threats of the day. The 1950s and 60s, for example, when nuclear war was the major threat, gave rise to films such as On the Beach (1959), Panic in the Year Zero (1962), The Lord of the Flies (1963), and Fail Safe (1964). And much has been written about how the current crop of YA dystopian books and films, The Hunger Games (2012) and its sequels, Orson Scott Card’s book Ender’s Game and the 2013 film version, and Divergent (2014), are as much about young people facing off against class and technological structures beyond their control as anything else.

Rollerball belongs to a different strand of dystopian cinema, depicting future societies in which order is maintained and/or the population entertained (they are often the same thing) through violent mass media events. Rollerball’s core message about the perils of a population anesthetised by entertaining spectacles, and the resistance of one individual who has triumphed in a sport designed to display the futility of individual effort, seem obvious now given the subsequent rise of reality television.

But this strand of film also taps into an deeper theme, characterised by Andrew O’Hehir in a 2012 article in Salon, as ‘the idea that our species remains cruel and barbarous at heart, that the strong will always rule the weak by whatever means necessary, and that our collective obsession with sports and games and other forms of manufactured entertainment is a flimsy mask for sadism and voyeurism.’

Rollerball wasn’t quite the earliest of these films. That distinction belongs to British born director Peter Watkin’s little known 1971 effort, Punishment Park. Filmed in semi-documentary style, it depicts an alternative America in which those judged risks to internal security – feminists, anti-Vietnam War and civil rights activists, Communist party members – are arrested and given the choice of going to prison or spending three days in a stretch of desert called ‘Punishment Park’, where they are chased by National Guardsmen and police as part of their field training. If the prisoners can avoid capture they are freed; if not, they are thrown into prison.

In addition to The Hunger Games and its sequels, other entries in this canon include Logan’s Run (1976), The Running Man (1987), Japanese director Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale (2000), and Series 7: The Contenders (2001).

Logan’s Run is set in an apparently idyllic post-apocalyptic future in which poverty has been eradicated and everyone lives in peace. Order is maintained via the belief that when each person turns thirty they are reincarnated into another life cycle. The process of ‘renewal’ occurs via a public ceremony referred to as ‘carousel’. Few citizens know the reality: that instead of being reincarnated, individuals are vaporised, and those who try and escape are hunted down by professional killers.

Based on a novel written by Stephen King, The Running Man portrays an authoritarian America in which the highest rating TV show features convicted criminals who try and escape death at the hands of professional killers. Battle Royale is set in a fascist Japan in which antisocial high school students are transported to an island where they are forced to hunt and kill each other. The contestants in the documentary-style movie Series 7 are ordinary people selected at random in a nationwide lottery using government-issued identification numbers. The main protagonist, Dawn, is a low-skilled woman whose determination to win the game stems from her desire for the prize money to take care of the child she is eight months pregnant with.

The most fascinating aspect of the current wave of dystopian film and literature is the closing gap between speculative futures and actual events. Earlier this year, I attended a discussion at Melbourne’s Wheeler Centre about climate change and fiction. One of the participants, the author of a recent novel set in a future Australia dealing with the impact of climate change, described his alarm upon learning the climatic shifts he was writing about in his novel, which was set in the future, are actually happening now.

It took forty years for the digital age to throw up scenarios similar to those depicted in Rollerball. Contemporary science fiction dystopias feel increasingly less like fiction and more like reality.