In a recent edition of his podcast Waking Up, Sam Harris differentiated religions and cults in this way: ‘Every religion is a kind of cult – it just has more subscribers.’ A million members will get you a religion, a hundred (or, in the case of Heaven’s Gate, just forty) a cult, with all the stigmatic baggage that label brings.

Harris’s neat aphorism leaves much to be unpacked, not least of which is the implication that a complex and significant question can be reduced to, in essence, a numbers game. I strongly suspect that if you were to conduct a poll on what constitutes a cult, most people would reach for a qualitative rather than quantitative definition, one that had nothing to do with numerically expressed popularity and everything to do with what we may as well call ‘theological content’. In other words, most people would, if asked, set cults apart from religions on the basis of belief – the more ‘out there’ the dogma held by any given group of religionists, regardless of their number, the more likely it is we’re talking about a cult.

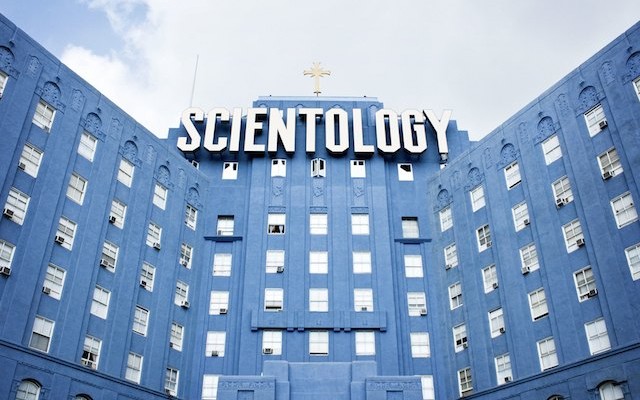

The crux of Scientology’s belief system, established by founder L Ron Hubbard in the 1950s, is becoming increasingly well known, especially its creation myth that the Church teaches to members sufficiently advanced (not to mention paid-up – more on this later) in their studies. By any objective measure, this myth and its surrounding doctrine – a hodgepodge assembled from aspects of pulp sci-fi, pseudoscience and psychotherapy that, as much as anything else, functions as a portrait of Hubbard’s troubled mind and idiosyncratic grievances – is outlandish. Coupled with its famously transparent financial motives (‘I’d like to start a religion. That’s where the money is!’), Scientology’s teachings seem to defy the idea that anybody except the most credulous, unintelligent or psychologically vulnerable among us could accept them in earnest.

And yet, if anything strikes one about the former Scientologists whom Alex Gibney interviews in his documentary Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief, it is qualities that run in the opposite direction. Almost without exception, Gibney’s subjects are both insightful and sceptical – even those who once held important positions within the Church’s hierarchy, such as Mark Rathbun, who was for a time second only to Hubbard’s nominal heir, David Miscavige.

A kind of cognitive dissonance swept over me as I watched them speak. Who, I thought, could be saner, and yet here they were, recalling years – and many thousands of dollars – expended not merely promoting a manifestly science-fictional belief system, but waist-deep in all sorts of ethically dubious behaviour from intimidation and obsessive litigation to extortion and physical (though apparently not sexual) abuse.

It’s important to understand that, as Gibney’s documentary makes plain, these things are not aberrations but constitute Scientology’s modus operandi. It is unique in the aggressiveness with which it attacks and smears its critics, and in one other significant respect too: its base financial scheme. Known as auditing, it is essentially a pay-as-you-go form of talking therapy that allows, according to Gibney, the church to amass large amounts of confidential information about members and use it to effectively blackmail them into not criticising or leaving the religion. Auditing sessions can cost, according to some testimonies, as much as US$1 per second.

The question of whether Scientology is a religion or a cult is not simply a semantic one. A religious status brings with it a suite of real-world benefits, not the least of which is tax exemption, conferred on non-profit religious organisations because it’s presumed they deliver useful social services to the community. In 1993, Scientology, with an arsenal of over 2000 lawsuits, won a long-running battle with the US’s Internal Revenue Service and was rewarded with a tax-exempt status. (No doubt Scientology’s shrewd deployment of the language of human-rights theory in its rhetoric did not do any harm either.) By contrast, in 1999 the UK’s Charity Commission ruled that: ‘the organisation [Scientology] was not established for charitable purposes or for public benefit and so could not be registered as a charity.’

These questions have not escaped Australia’s legal system. A 1983 Victorian Supreme Court judgment held that Scientology was:

no more than a sham. The bogus claims to belief in the efficacy of prayer and to being adherent to a creed divinely inspired and also the calculated adoption of the paraphernalia, and participation in ceremonies, of conventional religion are no more than a mockery of religion. Thus scientology as now practiced is in reality the antithesis of a religion.

The High Court quickly overturned this ruling, stating: ‘The applicant has easily discharged the onus of showing that it is religious. The conclusion that it is a religious institution entitled to the tax exemption is irresistible.’

Here were two lawful judgments then, handed down in the same year, which reached precisely contrary conclusions. Which was correct? Was Scientology a religion or, as the Victorian Supreme Court judgment had it, a travesty? What’s interesting about the conclusion reached by the Supreme Court is the extent to which it could serve not only as a repudiation of Scientology but also as a pretty good working definition of any orthodox religion. After all, are not a questionable belief in the efficacy of prayer, adherence to a supposedly divinely inspired creed, and participation in paraphernalia-rich ceremonies fundamental precepts of most of the world’s major faiths? Scientology, after all, has not even been around for a century and, while its membership appears to be in decline (in the 2011 Census, more Australians identified as Wiccans than Scientologists), who can say what the organisation will look like should it endure for 2000 years? The only certainty, as Chinatown’s Noah Cross knew, is that there’s nothing like age to lend a patina of respectability to even politicians and ugly buildings – and beliefs such as transubstantiation that, despite their farfetchedness, have become widely accepted tenets of mainstream religious doctrines.

To be sure, Scientology’s belief system is different in important ways from those of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, just as the belief systems of each of these religions is different in important ways from each other. But the more we emphasise Scientology’s absurdness, the more we lose sight of the correspondences that, in the end, may be far more pertinent. This is why Gibney’s documentary is useful – not only because it does a ‘wrecking-ball job on Scientology’, but because it exposes the power of faith to make otherwise sensible people believe in, and act upon, patently nonsensical ideas. More importantly still, it reminds us that there is nothing quite like a religious veneer for evading taxes or the proper scrutiny of human folly and misdemeanor at its most objectionable.

Let us say that Scientology is not a cult, but a very small religion – no more and no less deserving of the kind of free rides we’ve been handing out to other faiths for far longer.