There is something especially abhorrent about propaganda aimed at children. You don’t need to share in the belief that hatred must be taught in order to recoil when it is peddled to young minds. Yet the manner in which this is done is deserving of careful attention and study.

Consider for instance how gender discrimination was – and is – perpetuated in school texts even in relatively liberal societies. Those messages, which are borne of and lead to oppression, have to nonetheless seem positive in order to be viable for the instruction of children. In the 1970 American children’s book I’m Glad I’m a Boy / I’m Glad I’m a Girl, for instance, having gender-conventional aspirations guarantees both collective happiness and individual fulfilment.

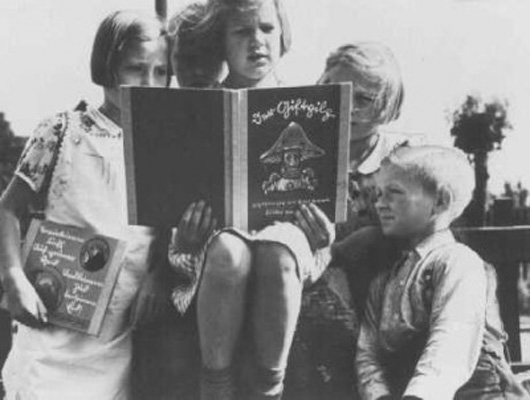

Fostering explicit hatred for specific groups can be a more difficult matter. In Christian Sunday School, deviations from accepted social behaviours might be presented as attributes of the devil, therefore a threat to the overall order. But the mass-hysteria of anti-semitism required more than cautionary admonishments or the appeal to lines in the liturgy of the day about the crime of deicide. This gap was filled by books like Der Giftpilz (‘The toadstool’), in which a mix of fear and hate for Jewish people was inculcated into German children via a sequence of horrifying moral vignettes.

Image via the United States Memorial Holocaust Museum

Along similar lines, the reinterpretations of The Story of Pinocchio in Fascist Italy served the dual function of contemporary propaganda: to establish and glorify the virtues of the perfect Fascist citizen, on one hand, and to caricaturise domestic dissenters and foreign enemies, on the other.

The literary scholar Luciano Curreri recovered and published four such texts in his 2008 book Pinocchio in camicia nera (‘Pinocchio wears the black shirt’), and they make for chilling reading. I alluded before to The Adventures and Punitive Expeditions of Fascist Pinocchio, which picks up some years after the end of Carlo Collodi’s book, although the protagonist, mysteriously, is still a marionette, and sports a permanently elongated nose, likely for the purposes of a virile visual pun. This was published in 1923, which is to say during the beginnings of the regime. The last reinterpretation, Pinocchio’s Journey, is dated 1944, and is as bitter as The Adventures was brash in its call for Italians to uphold their honour and fight to the end on the side of the formerly allied, now occupying, Nazi army.

Within the arc that separates these two texts is a catalogue of Fascist doctrine that is barely infantilised, insofar as the rhetoric of the regime addressed the adult population as children to begin with. But with a twist: that the core messages – anti-communism, racism, praise of black-shirt violence and the imperial wars in Africa, necessity not to ‘betray’ Hitler after the armistice of 1943 – were re-coded inside a story so well-known as to have achieved the status of universal popular myth. In fact The Adventures of Pinocchio – even before these Fascist interventions and Disney’s radical 1940 reimagining – started being retold almost as soon as it was first published as a book, in 1883, as various authors and publishers sought both to ride its popularity and to domesticate its intractable, apparently contradictory, moral messages.

In an inversion of the trajectory of present-day Hollywood remakes, it was Carlo Collodi’s original that was the dark, gritty fable, full of dread, arbitrary punishments and cynicism concerning the prospects of the newly-unified nation. Whereas the reinvented Pinocchio must cast off all doubt and embrace the optimism of the Fascist will, through a knowledge that comes not from books or education, but from the heart, that the cause of his violence is just. This is the Pinocchio of 1923, who inflicts lesson after lesson upon the cowardly Red, forcing him to gulp down castor oil, the ritual humiliating punishment of intellectuals and other opponents to the regime.

That shocking cover image of Pinocchio as a black shirt ‘punisher’ encapsulates the aim of this version, which is to glorify Fascist violence. The 1927 Pinocchio Among the Balillas is a smidgen more faithful to the source by re-tracing the old didactic route, and chronicling the puppet’s trials as he learns to abandon his lazy, wanton ways and accept to be recruited into the paramilitary corps into which Italian real live boys were automatically inducted as they went to school.

During the imperial phase of the regime, when Mussolini proceeded to secure the nation’s ‘place in the sun’ by means of a series of ferocious military campaigns in Africa, the pedagogy of Fascism turned towards painting the portrait of the colonised peoples as meek, cowardly simpletons barely deserving of the privilege of becoming Italian subjects. The farcical Pinocchio Tutors the Negus contributes to this effort. At the outset, Pinocchio accidentally blackens his face while stealing chocolate, and the robbed shopkeeper shouts after him ‘catch him, the Abyssinian!’ Astoundingly, the book goes downhill from there.

But the most horrifying and altogether tragic of Curreri’s finds is Pinocchio’s Journey. Published in 1944 – which is to say during the Nazi occupation of Italy – this version chronicles Pinocchio’s growing discomfort as he witnesses his compatriots celebrate the fall of Mussolini and cheer for the liberation of the country by the Allied forces. By making no mention of partisans and the Resistance, Pinocchio’s Journey portrays the civil war as a choice between fighting alongside the unjustly maligned former ally or cravenly waiting to be invaded by the former enemy. Rejecting the entreaties of the Cat and the Fox, Pinocchio chooses the former, and – in the book’s most arresting scene – implores an SS officer to take him as a volunteer.

The officer need not reply: what use could a marionette possibly be to the mighty German army? Yet Pinocchio, as if in a grotesque vision, has his wish granted as the Blue-Haired Fairy sends for a dove to carry him to the battlefield. Thus, as the last line of the book triumphantly declares, he will finally become not merely a boy, but a man.

There are many sinister echoes of this, the wrongest of all versions of Pinocchio, in the Berlusconi-era wave of revisionist films and books aimed at rehabilitating the Italians who chose to side with Nazism in our two-year civil war. There is also a shred of sardonic truth in its warning that the erasure of the symbols of the regime – which began in earnest the day after Mussolini was deposed – cannot, will not by itself remake our history. The Fascist Pinocchios, then, are as much a ghastly document of the past as a creepy premonition of what might yet be, in a nation as bad as remembering its history as its fables.