Not long ago, the New York Times ran a travel feature on Perth that concluded the WA capital was a ‘hipster heaven’ that embodied ‘all things right about cities’. The article was widely shared by locals on social media, with a combination of awkward pride at having been noticed by the outside world, bemusement at its overblown praise, and a comfortably distancing snark.

Filmmaker Jimmy the Exploder lamented in the Guardian that his former hometown remained ‘a frustratingly conservative, culturally-starved, unaffordable backwater’. Blogger Nik Barron noted that this ‘rare flurry of conversation about Perth’ was limited in scope: there was little space for serious questions about racism or growing inequality.

The mixture of sentiments evoked by the article was certainly familiar, though. Among many twentysomething and thirtysomething residents, a set of questions plays out time and time again: when are you leaving? If not, why not? Are all your friends moving to Melbourne too? Yes, it’s nice here, but isn’t there something missing?

Perth is known as the most geographically isolated capital city, but the place has also been less flatteringly captioned: it is seen as something of an intellectual paddling pool, attracting sobriquets of ‘provincial backwater’ and ‘cultural wasteland’.

Dismissive attitudes to the sprawling city arguably represent a continuation of the ‘scorn for the suburbs’ that James Button described as ‘a staple of Australian cultural life’ in The Monthly last year. Six degrees of separation can be more like three or four; the city is too small for honesty, as one band sang in the early 2000s. It’s a place with only one daily newspaper, enjoying a less widely dispersed cultural and intellectual capital than other major cities. Watching events in Sydney and Melbourne unfold in live time via Twitter is sometimes apt to induce pangs of envy.

Still, Perth might not be Paris, but it’s hardly a remote sheep station either. It’s actually a pleasant place to live (providing, of course, you’ve money to spend), we’re not lying about the quality of the beaches and if you’re struggling to find something to do of an evening you’re probably not looking very hard. Assertions of an essential difference between Perth and its equivalents in Victoria and New South Wales are undoubtedly based in truth, but also reflect the narcissism of small differences.

Reactions to the cultural wasteland tag are mixed, including tedious debates over whether Perth can be described as ‘Dullsville’, a rather obnoxious ‘Boomtown’ swagger, and perverse satisfaction in differing from ‘the Eastern states’ (which admittedly has its advantages).

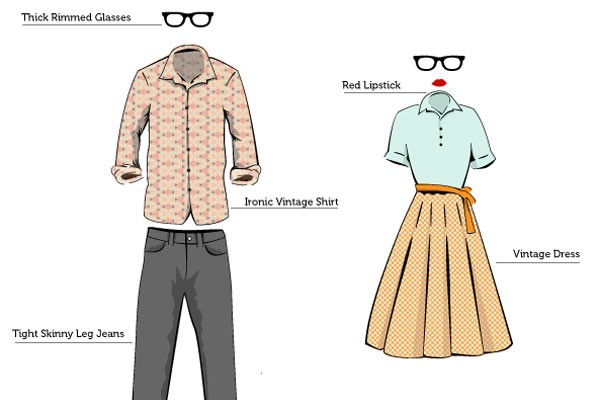

In 1950, AA Phillips defined ‘the cultural cringe’ as the tendency of Australians to ask themselves of any local achievement: ‘Yes, but what would a cultivated Englishman think of this?’ The habit has not disappeared, but over here has additional layers: some Perthites wonder how those sophisticated bastards from over east might view our triumphs, inculcating a defensive instinct to rattle off indicia of cosmopolitanism, list ‘our’ small bars, and gloat over articles like the NYT feature.

A more pernicious consequence of the sneering about Perth (by inhabitants, outsiders and the Brunswick- or London-resident diaspora) is that it exacerbates a certain attitude within Western Australia: chip, meet shoulder. This sentiment can be convenient to politicians and we will doubtless see more of it as the senate vote approaches; already the premier has characterised Bill Shorten as ‘another eastern stater bagging Western Australia’.

More abstractly, there is the notion that WA residents are somehow more authentic than those who scoff at us. The obverse of the innately-conservative-philistines-who-pause-in-our-obsession-about-material-goods-only-long-enough-to-glass-each-other stereotype is the more benevolent one in which we are painted as salt-of-the-earth types. This notion is linked to something bigger – a tendency to view rural Australians as superior to city-dwellers, so that the further one ventures from our major cities, the realer things become.

It’s tempting to buy into notions of our own authenticity, but best to guard against this tendency in the interests of clear thinking. Frankly, Perth is not Karratha, Kalgoorlie or Paraburdoo and it’s self-indulgent for us to carry on as though something earthy or exotic sets us fundamentally apart from Australia’s other major cities.

At its worst, the tendency to view WA as a state apart simply leads to wankers in Perth complaining about wankers in Sydney; it’s a bubble insulated from self-awareness. The performance of Western Australian exceptionalism reaches its zenith when locals talk possessively of ‘our iron ore’ – as though the distribution of minerals between states reflected more than luck and geography, and the resources extracted from the Midwest and the Pilbara had some sort of mystic connection with suburbia.

It’s easy to be overly harsh about home, though, and we can despair of parochialism while also rolling our eyes at the ‘cultural wasteland’ label. The periphery brings its own benefits, the distance and endless skies reminding us of our own smallness in a complicated world. After all, it is not wrong to feel affection for a place, provided one loves wisely and not too much.