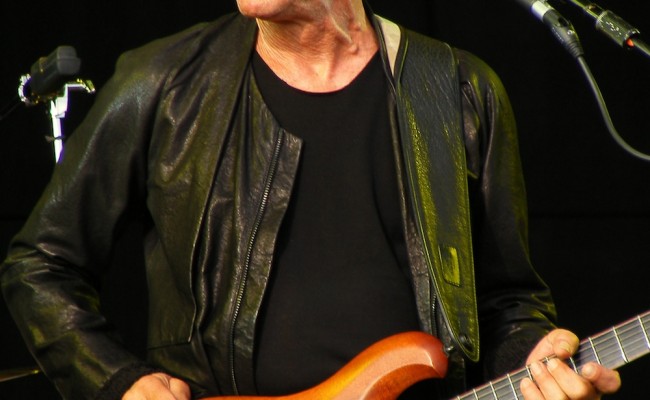

Years ago, the Age was wont to put out a parody edition at the time of the Melbourne Comedy Festival. Last fortnight, I thought they’d returned to the habit, with six articles – six! – on the recently passed Lou Reed (and a double page spread on hot new restaurant Chin Chin).

The coverage was part of the wall-to-wall celebration of Reed that consumed large sections of the culture. Those of us who wrote something more historical and critically reflective – about an iconic pop star whose decade or so of innovation had long since decayed into cultural muzak – got snapped at by boomers and Gen Xers at the boomer end of the scale.

The paradox – honouring a punk pioneer with garlands heaped high – reached its apogee on, inevitably, QandA, when the panel was asked to make a more or less ritual obeisance to the genius of Lou. Chrisstopher Pyne was met with howls of despair when he said that Reed was a ‘heroin addict who appealed to transgressive ABC types’. In other words, the only genuinely punk response to Reed’s passing was held to be a disgrace to his memory.

The Reed exequies were simply another moment marking a transition from one era to the next, a fundamental shift many of us have lived across.

The cultural surface of that move is described easily enough. From roughly the 1830s to the 1970s, the rise of bourgeois culture and its norms was accompanied by a parallel rise in an antinomian ‘bohemian’ culture. The name was taken from the French word for Roma people, and the bohemians only emerged as a distinct category when aristocratic culture – that of the dandies and courtiers – had thoroughly disappeared.

The bourgeoisie defined themselves against the aristocracy – life and time were work; love and pleasure was suborned to duty; individualism was expressed through accumulation, etc. The bohemians adopted the aristocratic ideal – that life should be lived freely, immediately, viscerally – and perfused it through art, as the pursuit of genius.

The aristocratic/bohemian ideal brought all the radical strains together, becoming the imaginary ideal of the period. Marx and Engels’ picture of communism at the end of the German Ideology – ‘hunting in the morning, fishing, criticism, blah blah’ – is both an appeal to the aristocratic idea of life as a communist one, as well as a gentle parody of it.

For a century-and-a-half, through the rise of industrial capitalism, this dynamic held sway. The boho tribes – from Bloomsbury to the Beats – were miniscule groups compared to the forms of mass life imposed on the two great classes. By the 1960s that started to shift, as expanded education, the boomer demographic bump, and the great liberal political explosion after the Second World War, created what we know now as the 60s.

That total moment – when everyone could be bohemian – remained to a degree outside the cultural-economic process. But its massification meant that the boundaries of transgression – bohemia’s defining edge – were quickly reached. Punk was the final moment, a rebellion even against the humanist and loving themes at the base of the bohemian ideal. Punk in its purest, most anomic form – not the leftish punk of the MC5, say, but the celebration of atomisation, fetishism and power in the music of the Velvet Underground, its celebration of death via the figure of heroin – was bohemia’s bohemia, the final turn.

Bohemia proper, the 60s, the last outside, was dragged inside over the next thirty years. The transition in the West coincided exactly with its outsourcing of industrial production to the East, and the hollowing out of the core class conflict, with the collapse of socialist models and legitimacy in the 70s, and with the fusion of information technology – first PCs then the ‘net/web – with capital, across the 80s and 90s.

Today, the humanist/communist utopia of bohemia, has been entirely incorporated, not so much traduced but realised. Living off mining (Oz), banking (UK), and debt (US), culture is the primary means of production and reproduction, even when it comes in the appearance of older forms. Those from the 60s are now in their 60s – below them, two generations formed within a bohemian-bourgeois economy have created a vast new world with no outside, no edge.

These new classes are the new engineers, the pillars of the economy, the centre of the new world. Yet this is the paradox: these new classes and groups cannot define themselves by that measure, cannot regard themselves as solid centres of a new order. As cultural producers, their identity and sense of meaning relies all the more on identifying with a transgressive edge that has now vanished – all the more when their cultural role is the exact opposite of transgression.

By the time of Lou Reed’s death, the 60s had been so memorialised, reproduced, reconstructed and represented as to have exhausted the fund of cultural meaning altogether. Lou Reed’s work had been a part of that – pressed back into service by the appearance of ‘Perfect Day’ on the myth-busting-creating heroinoir Trainspotting, he soon became omnipresent. Does anyone now need to hear ‘Perfect Day’ ever again? Still less ‘Walk on the [Damn] Wild Side’?

Of course not. Nor did there seem much spontaneous joy in the memorials. Something dutiful was being performed, some solid work was going on; it was, in all its propriety and application, bourgeois in the extreme. Were you to obscure the dates, you’d be hard-pressed to tell the difference between the obituaries for Reed and those for Ruskin, a century ago.

Lou Reed’s death is now the site of a further crossover. Because the transgressive edge has been lost, its discovery – in memory only – must be done as work, which undermines its vestigial meaning, pushes it further away. The whole process seems a second-order nostalgia now – a nostalgia for the nostalgia the culture used to be able to feel about its last transgressive moment.

Why are we in this impasse and how do we get out? The obsessive backward glance by a social class that should be at the cutting edge of creating a new world – that of socialism, of a real freedom – occurs because a truly radical future cannot be imagined as an everyday thing – and is, in some ways, not wanted.

We have lost familiarity with the idea of intellect and culture as building the world – submerged as they’ve become in power and commodification – and so the cultural/knowledge class, faced with the impossibility of imagining coding in the morning, cyber-performance art in the afternoon, etc, harks back to a time when it had an inside, an establishment to define itself against.

When does it end? It ends when the frameworks within which that class exists come to crisis, and there is no way to avoid turning towards the future – at which point nostalgia becomes history.