In Adelaide for business, changing hotels, waiting in the lobby, thinking about my impending divorce, replaying some months in my head wondering if it could have been otherwise. Remorse and regret.

The cab pulls up, I load the bags in. It’s a short hop, from South Terrace to North Terrace. Driver’s old, small. Neat Ze Chanzellor, hmmmm … as we turn out of the forecourt. The fabled Adelaide accent, with a touch of German?

‘You Adelaide born and bred?’ Pause. No, no. Pause. ‘Where are you from?’ Pause. Poland. Poland then Germany. I been here a long time. Born in Poland, then eight years in Germany. Pause. Then, unbidden, I was born in ’39.

‘So just before the war?’ He seems surprised that someone knows the chronology. Yah yah, born five six thirty nine. Then the invasion. Then Germans made my parents go to Germany to work, they said ‘leave him with his grandmother’ and when I was four they came back to get me.

I was picturing work camps, death camps – but came back to get him? ‘Where did they, I mean how —’ The worked on a farm, they were billeted there. That doesn’t sound so bad, all things considered.

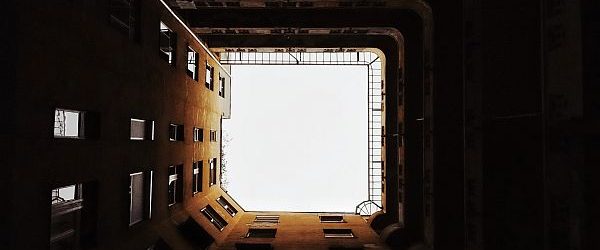

We should be there by now, but the morning traffic in the Adelaide grid has slowed to a crawl. The city: low-slung, archaic, marooned in the 70s, a little historyless. In the cab, otherwise.

‘So they made it through the war?’ What? No. Wrong question. My mother did. Pause.

Unbidden: My father used to listen to the radio, the BBC, which you weren’t supposed to do. The war now so far from here that he cannot assume what I will and will not know. Someone reported him and one day the Gestapo came, came in a big black limousine, and we never saw him again.

We’re still three blocks away from the hotel. They came for my mother first they thought it was her. They took her away then they brought her back. Pause. I was five. ‘Did you know? Did you understand what was going on?’ Well I mean there was so much going on.

I meant his father. I rephrase it a couple of times but it doesn’t take. Then, We found out. Later. He was in a camp. When the Russians came forward the Germans moved the prisoners onto a boat. The British started bombing it. The prisoners put up white flags, but the sailors took them down again and the boat was sunk.

We turn into Hindley, the world’s last bohemia – go-go bars next to secondhand bookshops, more from that older world than this one. Blue sky, sun even and bright on the windscreen, flashing as we pull up. She married again after the war, in the camp. Eight kids. An even tone.

Was he loved by them or left out, precious gift or reminder of what could not be forgotten in a new life? I had started a chat out of curiosity over a twang in the voice, and, within a minute, had been dropped into midnight of the twentieth century. Or it had dropped towards me – that woman, that man. The questions kept coming as I hauled the bags out, almost an interrogation: Did she give him up out of terror? Did he blame her for doing it? What was it like on that farm, afterwards, with a five-year-old with questions? Maybe they never got on. Was part of her pleased, and she hated herself for that? What did he think, later, as the waters closed over?

The fare’s eleven dollars, I have it exact. A keep-the-change-tip would be fine, but to add a dollar would be, what – thanks for the story, got any others? Then, the usual American courtesy sign-off after a cab conversation: ‘nice talking to you.’ Blackly funny as a departure.

Ten minutes later, I’m thinking about my divorce again. Remorse and regret. Source of light at the speed of light, there is no standard measure. Travelling through the dark, it’s relative to the frame – eighty years, five minutes, some months, midnight, the dazzling present.