Jim Shepherd recently passed away at the age of 80. It is appropriate to consider his contribution to Australian popular culture. A former sports journalist, Shepherd was a keen follower of motorsports and recognised as one of its premier historians. But what he’s most remembered for he came to rather late. For the past 25 years, Shepherd had been sole owner of Frew, the company which published The Phantom comic book in Australia.

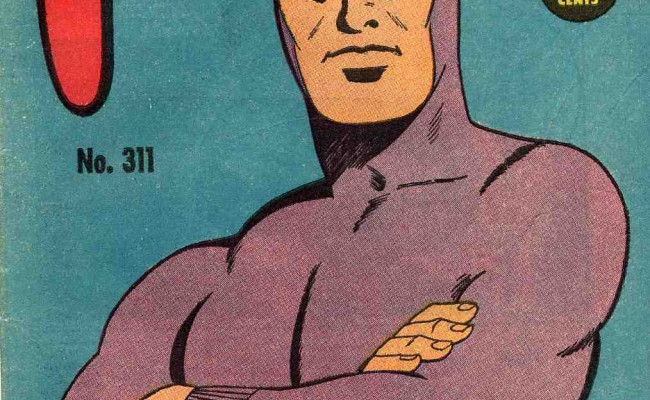

This year, Frew will likely publish its 1,700th edition of The Phantom. That makes Frew the most successful Phantom publisher in the world by far, and The Phantom both the longest-running Australian comic book and one of the longest-running surviving Australian magazines of any type, just behind such staples as Women’s Weekly, Meanjin and Southerly. The Phantom has occupied shelf space in Australian newsagents since the immediate post-war years, when he competed for attention with Ginger Meggs and Dick Tracy.

Of course the Phantom is not an Australian character, but it’s surprising how many people think he is. ‘I never let them know otherwise if I can avoid it,’ quipped Shepherd when I met him some years ago in his office overlooking Hyde Park in Sydney. The Phantom is Australia’s favourite comic hero, regularly out-selling the flashier, glossier Batman, Superman and Spiderman by as much as ten-to-one. ‘Even though we are pensioners and battlers,’ wrote Doris Dawe of Glenelg, South Australia, in 1994 in a letter to Frew that defies satirical treatment, ‘we always find the money to buy The Phantom.’ And it’s not just a favourite among Dorises from Glenelg. The magazine’s occasional ‘Phantom Forum’ section – in which is published, according to Shepherd (a wily ad-man of the old school) a mere fraction of all fan letters he receives – contains correspondence from children, teenagers and adults young and otherwise.

Prominent Australian ‘phans’ include actor Jack Thompson, singer-songwriter Josh Pyke, and Bill Lawry, the former cricket captain turned commentator who apparently acquired the nickname ‘Phantom’ on tour in England in 1961 because he carried around comics in his kit-bag. Wally Lewis and Bob Hawke are also known for their love of the character, and university corridors are filled with academics who harbour a secret passion.

The Zane movie – the Phantom’s official cinematic feature debut after a handful of unauthorised Turkish productions in the late 1960s – was filmed in Australia and directed by Simon Wincer, of Phar Lap and The Lighthorsemen fame. This is the only country in which the 1996 film did not flop commercially. In 2000, just over one-fifth of all Phantom newspaper syndication worldwide was in Australia.

Why is it that the Phantom has this status, here, in this country?

•

Like all commercially successful costumed superheroes, the Phantom is an American creation. But unlike Batman (Gotham City), Superman (Metropolis) and Spiderman (a de-euphemised New York), the Phantom doesn’t live there. His home is a Skull Cave, deep in the jungles of a fictional African country called Bangalla.

Creator Lee Falk (1911–1999) gave the character not just an ‘origin’ story, but a whole heritage, a mythos. For Those Who Came In Late:

Four hundred years ago, a man was washed up on a remote Bengal shore. He’d seen his father killed and his ship scuttled by Singh Pirates. He swore an oath on the skull of his father’s murderer ‘to devote my life to the destruction of piracy, greed and cruelty …’. He was the first Phantom, and the eldest male of each succeeding generation of his family carried on. As the unbroken line continued through the centuries the Orient believed that it was always the same man!

‘Our’ Phantom, as phans know, is the twenty-first in the line. Human, and without the ‘super powers’ which were to become the staple of American comic-strip characters during the nuclear 1950s, our Phantom is married (to Diana, a former socialite, Olympic diver and karate black belt who now works for the UN) and, since 1979, with children.

The Phantom almost didn’t make it into the jungle. Falk originally imagined him as Jimmy Wells, a rich American playboy with a double-life as a night-time crime fighter. Had he persevered with the Wells plot, the world may not have known Batman, who appeared as Bob Kane’s creation in Detective Comics three years after the Phantom first made the newspapers. The writer Kai Friese speculates that Falk’s last-minute jungle switch ‘probably cost the Phantom his place as an icon of the American century’.

Action comic aficionados will be aware of the way characters and storylines have changed to reflect prevailing domestic moods in the United States since the 1930s. Superman began life as an unbeatable New Deal poster-boy, fighting for ‘truth, justice and the American way’. Batman was a unique take on the popular pulp detective fiction of the 1920s and 1930s. During the 1950s they were both drafted into the Justice League of America to help fight radioactive aliens and other Cold War-inspired monsters. The 70s saw them more concerned with the social causes of street crime, and since the 80s their own personal demons have led them into existential crises of the kind that surely made them yearn for simpler times, when the Manichean distinction between good and evil was still possible.

Perhaps by virtue of the Phantom’s home outside America, its social trends have largely passed him by. Instead, his unique location has tied him, more than most costumed superheroes, to the global events and politics of the twentieth century. And by virtue of Falk’s use of a genealogical heritage, while he has a second home in the USA thanks to Diana’s origins, the Phantom’s mythology is tied to the Old World, to Europe. ‘Bengali’ – Bangalla’s former name before it emerged that such a place actually existed – was still a colony when Falk, then aged 24 and an aspiring theatre producer and director, first developed his character for King Features Syndicate in 1936. ‘Bengali’ was originally somewhere on Java, and while working as a propagandist for an Illinois radio station and in the United States’ Office of War Information, Falk wrote the Phantom into World War II, leading an allied defence of jungle peoples against the invading Japanese. Sometime during the 1940s, Falk moved ‘Bengali’ to India, and after that newly-independent nation became less idealised in the Western imaginary during the turbulent 1950s, Falk shifted Phantom country to east Africa. As the Winds of Change swept Africa, ‘Bangalla’ achieved independence and elected the humanist intellectual Lamanda Luaga as its inaugural president – only to suffer a succession of dictatorial coups thereafter.

•

Post-colonial critics typically find little to celebrate in Falk’s surface updates. Despite living in the ‘deep woods’ for more than four hundred years and twenty-one generations, the Phantom has nearly always married a white woman, invariably from Europe (although in the American century, Diana is from New York). While the references to ‘natives’, cannibalism and ‘superstitious tribal nonsense’ are long-gone, the Phantom remains a white man administering justice and wisdom to the dark-skinned locals. With their superstitions, they revere him because they believe him to be centuries old, but we, the (invariably white?) readers, are in on the secret. And although supportive of Bangallan self-determination, independence and democratisation, his anti-racism – temporarily suspended for the war against the ‘Nips’ in 1942 – can seem today a cringeworthy and uncritiqued paternalism. The Phantom is the bearer of democracy, the rule of law and modernity to the jungle tribes. Perhaps one reason the Phantom has never quite achieved iconic status among Americans is that he is too stark an embodiment of their own imperialism, which they prefer to deny.

This is not the Phantom’s problem, however. He lives in a jungle which is unexplored, whose tribes are largely uncolonised, uninvaded, unsanctioned. He brings democracy and peace in a spirit of benevolent altruism – he serves and takes nothing in return. His material wealth is boundless, in the form of priceless jewels rescued from pirates by his ancestors, and it affords him a post-materialist consciousness and an opportunity to engage with the jungle tribes outside of the question of resources – a question which is always getting in the way of black-white relations in Australia. Many non-Indigenous Australians would like to imagine their contact with the ‘tribes’ of this land in Phantom terms. Is this what we like most about the Phantom? Do white Australians still see themselves as the Ghosts Who Walk of their own region, deputy sheriffs keeping the peace among tiny Pacific nations and modernising the local tribespeople – the Aborigines – by extolling the benefits of Civilisation while eradicating their more distasteful cultural practices?

If Superman is the ideal of American justice domestically and internationally, the Phantom may be the ideal of white civilisational colonialism, the colonial fantasy. Virtuous and selfless, he modernises the jungle tribes at the same time as he protects and defends the ultimately hapless tribespeople from modernity’s darker trends. Since the 1970s he has often exposed the practices of companies which exploit local labour, mine resources without authorisation and illegally dump their toxic waste. White-skinned criminals are treated just as harshly as black-skinned charlatans masquerading as witch-doctors. And, perhaps most importantly, Bangalla’s tribespeople accept without tension the imposition of a modern legal structure and a scientific world-view while remaining cultural villagers.

If this is racism, it’s of a more subtle kind than white Australians’ traditional definition. The Critical Race Theories of African-American scholars and the anti-colonial discourses of Frantz Fanon and the post-colonial critics have largely passed white Australians by, unless they happened to take a university course in literature or sociology or anthropology. In the popular mind ‘racism’ is evil, but its definition is restricted to its Ku Klux Klan or Cronulla varieties. There is simply no popular understanding, here, that what some call ‘racism’ is a form of insidious discrimination that lurks behind liberal discourses of ‘equality’.

On most white Australians’ understanding, the Phantom is not racist. In stories since the 1950s, Lee Falk regularly exposed the prejudice of whites who saw the jungle blacks as inherently backward. He gave some of his jungle people university qualifications, and often depicted them as – like the reader – ‘in’ on the ‘joke’ of their own traditions and superstitions. In a 1997 letter, a long-time fan expressed her desire for ‘a bit of the old mystery, frightened natives saying ‘Ghost Who Walks Who Cannot Die’.’ In his reply, Jim Shepherd assumed the high moral ground: ‘Things changed many years ago. The Phantom does not inject fear into ‘frightened natives’.’

•

Readers of The Phantom enter a world of deep, ‘unexplored’ jungle where ‘no white man has been’ and where the ‘dreaded Bandar pygmy people’ protect their territory with ‘poison-tipped arrows’, one scratch with which means ‘instant death’. But for all its affected terror, Phantom Country is a safe and familiar place for its readers, with its Skull Cave hidden neatly behind a waterfall as a child might hide a favourite toy under a pillow. A familiar and friendly cast of characters combines with a handful of well-known locations – like the beach of golden sand at Keela-Wee and the Phantom’s own island playground at Eden, where he has taught the carnivorous animals not to eat one another – to create a comfortable fantasy into which the reader can escape. It is a sanitised jungle, ideal for the armchair explorer and the daydreamer, where leeches and spiders and mosquitoes and illness don’t figure. It is after all a comic world, where heroes win and evil loses, where order is Good and equilibrium prevails.

The ‘Lost World’ genre has been one of the most enduring of modern popular literature, from Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines through to Michael Crichton’s Congo. In this genre, Africa and India are places of mystique and high adventure and romance, their dangers ‘thrilling’, their ‘native’ casts so thoroughly othered they may as well be Martian. It is no coincidence that The Phantom borrows many devices from the genre. Falk was a great fan of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Rudyard Kipling, in whose Jungle Book the Bandar pygmies have their origin. In Urdu, which Kipling learned from prostitutes, ‘bandar’ means ‘monkey’. Although the Phantom – like the West – eventually had to adapt to the Winds of Change, he was born into the world of Tarzan and Mowgli, not of Joseph Conrad and HG Wells. And while Lee Falk travelled far and often during his 88 years, he never went to Africa.

Australia has its own history of the ‘Lost World’ fantasy which informs the Phantom imaginary. Sitting alongside the developmentalist notion that the Aborigines were ‘dying out’ was the romantic duality of the barbarian and the civilised. This was the Australia described by the likes of Jack Idriess, the prolific writer who was as fascinated by Aborigines’ survival skills as he was passionate about outback development, in works such as Flynn of the Inland, Headhunters of the Coral Sea, The Wild White Man of Badu and Our Living Stone Age. In the Australian Lost World myth, Aborigines were living ‘relics’ of a past age, an ‘undiscovered’ world only now being mapped into the Modern. As late as 1984, nine Pintupi people made international headlines when they literally walked out of the desert as real-life, ‘primitive’ Aborigines.

The Phantom seems to belong to this earlier time. It is only in the past generation, through filmmakers (Richard Frankland, Warwick Thornton, Rolf de Heer, Rachel Perkins) and advocates and researchers (Noel Pearson, Patricia Anderson, Marcia Langton), that Aboriginal people are finding a place in the Australian consciousness which does not depend upon their Orientalisation into some unfortunate combination of noble savage, lost tribe, ancient mystic and drunken welfare bludger.

•

As appealing and persuasive as it might appear to post-colonialist theorists, however, it seems altogether too simplistic to put The Phantom’s appeal here down solely to a lingering colonial ‘phantasy’ in the minds of white Australians. And it would hardly account for the character’s appeal in places like Fiji, Brazil and India. Writing recently in the journal Transition, published by the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research at Harvard, Kai Friese recalls the popularity of The Phantom in Delhi, where he grew up. The Indian Phantom, printed by local publishers, shared many of Frew’s features. ‘The Phantom was a more dependable hero [than Superman or Batman], always there when you needed one – and cheap, at one and a half rupees. There were none of the cruel advertisements for unobtainable goods. The Phantom had matte covers and reassuringly crappy production values. He was a castaway on our side of the pond, a Third World kind of guy.’

Perhaps the most ‘Australian’ thing about the Phantom is his character. Thoroughly secular and rational, perhaps too much so for Americans whose Presidents are compelled to invoke a Christian god, the Phantom is as immune to believers’ babble as we like to think we are. And yet there’s a sacredness he nurtures, a relationship to the land which is as real as it is unremarked. The Melbourne academic David Tacey argues that Australians – even self-proclaimed atheists like Phillip Adams – possess a deep spiritual consciousness which can manifest, like it does in the Phantom, in a ‘fierce commitment to social justice’ and to ‘community’. Observes Tacey, whose research interests lie in psychoanalysis and spirituality: ‘The typical Australian gesture is to wipe all “talk”, all “pretence” about religion away, and then in an ironic reversal, to demonstrate those very religious virtues and values that one has just denounced.’ The Phantom, too, is at once dismissive of harmful superstition and deeply aware of custom and custodianship – and profoundly virtuous.

With his incorrigibly incorruptible moral and ethical standards, the Phantom might have been seen by Carl Schmitt as a secular Christ. But he is not miraculous. The Christ motif more properly belongs to Superman. Like Superman’s creators Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, Lee Falk (born Leon Gross in 1911) was the son of European Jews, but unlike Shuster and Siegel he took care not to let the religious subtext of his family’s new home infuse the character of his creation. The Ghost Who Walks is instead a modern and secular masculine ideal, whose moral purity has guided him through countless marriage proposals from beautiful princesses. So clear and pure is his moral conscience, so confident is he of Diana’s singular love and commitment, that he rarely experiences jealousy – even when they endured months apart during the 1950s and Diana the socialite would accept dates with rich and handsome gentlemen!

The Phantom’s anger is never uncontrolled, always appropriate. More often he is impossibly calm, even ‘laid back’, even during fist-fights. Do Australians like to see themselves in the Phantom where Americans can’t? Australians may recognise the not-quite-human stoicism at the heart of the Phantom’s character. Life’s vicissitudes do not bother him. He simply acts to make the situation right again, or adjusts to the new reality. He is practical, no-nonsense, fiercely egalitarian, just, honest, wry, quick-witted, unflappable, solitary, courageous, loyal and even shy with women. Long-time phans invoke the character’s famous dry humour with a kind of pride. He could be a creation of Russel Ward rather than Lee Falk. If Australians like the Phantom, perhaps it is because we recognise in him our national character, our Australian Legend.

•

‘There’s got to be a link between Scandinavia and Australia,’ Jim Shepherd mused when I met him, ‘and other than Abba, I’ve never quite worked out what it is.’ These are the two places where the Phantom is most popular. The Danish media company, Egmont, even commissions original fortnightly stories of its own, most of which Frew reprints, translating them in its Sydney office. According to Shepherd, one reason for the character’s popularity in Scandinavia and Australia is that he’s ‘a pretty nice guy.’

Shepherd liked to suggest an additional set of reasons for the character’s popularity here. The character’s decades-old syndicated presence in Australian newspapers has given him a just-below-the-surface ubiquity in the Australian vernacular. Editorial writers will often make passing references to aspects of Phantom lore, and the urge to link any mention of a ‘ghost’ with the act of ‘walking’ appears irresistible. The Herald Sun carried a story about Andrew Lloyd Webber’s sequel to his Phantom of the Opera musical with the headline: ‘Ghost who walks again.’ Trying to describe a recent fascination in poetry circles for the ‘pantoum’, a Sydney Morning Herald writer quipped that it wasn’t ‘the Ghost Who Walks, but the traditional Malaysian verse form.’ One of former Collingwood AFL footballer Simon Prestigiacomo’s nicknames was ‘the Phantom’ because, according to a team-mate, he was ‘the ghost who walks’ – he was ‘just that quiet he floats through and you wouldn’t even know he has walked past’. Often-absent Members of Parliament are frequently referred to as ‘the Phantom’ or ‘the ghost who walks’, including the ex-WA Liberal MLC Sue Walker, whose surname proved too tempting for the West Australian newspaper.

There is now a kind of intergenerational familiarity about the Phantom which, perhaps because of the continuous newspaper link – the three panels can still be found in most News Ltd papers and a raft of regional dailies – has escaped the Archie and MAD magazines. It’s there as well with Warner’s Bugs Bunny and Disney’s Mickey Mouse, but because of their talking TV presence they’re more recognisably American. When the Daily Telegraph quietly removed the daily strip from the paper’s comics page a few years ago the move provoked such an overwhelming reaction that it decided to just as quietly reinstate it.

The Phantom was introduced to Australians in 1936 – the year of the character’s first appearance in the United States – by the Australian Woman’s Mirror, which published the strip until supply lines were cut off in 1942. Here, perhaps, is the origin of the erroneous idea that the character is Australian: as was common at the time, the Mirror transformed Diana into a local lass and renamed places to suggest the action was happening here. It wasn’t until 1948 that Frew Publications was established in Sydney, its name an acronym of the first letters of the surnames of each of the company’s four founders.

Frew attempted to publish stories featuring other characters, with few successes apart from Mandrake the Magician, Falk’s other creation. In time, The Phantom became the company’s only line, its popularity insulating Frew from the broader decline in the Australian comic publishing industry after television began broadcasting in 1956.

By the late 1980s, the decades-old tradition of Australian publishers reprinting popular American titles like Batman and Superman – a tradition which dates back to wartime import restrictions – was all but dead. Children of earlier generations will recall the black-and-white newsprint reprints of DC and Marvel titles by Sydney-based advertising man Ken Murray’s company under such imprints as ‘Planet’ and ‘Murray’. But a combination of changing consumer preferences and the removal of import restrictions on overseas publications meant that by the late 1980s, Frew was practically the last local company producing reprinted, black-and-white versions of American originals.

Without the late Jim Shepherd, it’s doubtful The Phantom would have survived as a comic book in Australia. He became Frew’s sole shareholder, reluctantly, during the late 1980s, after he was asked by the company’s founders – Ron Forsyth and Jim Richardson – to fly to the United States on their behalf. His job was to placate the people at King Features Syndicate who were concerned that the newsprint reprints by Frew (the Australian licence-holder for The Phantom) were doing justice neither to the character nor to their corporate image. It became clear that King Features wanted certain undertakings from Frew if it was to continue to enjoy the Australian publishing rights. Receiving no replies to the faxes he was sending to the owners requesting instructions, Shepherd made a series of unsolicited guarantees to King Features in New York before returning to Sydney to find Richardson gravely ill and dying. He soon arranged to purchase the entire shareholding, and began to make small but effective changes to the publication in order to woo back lapsed phans.

Shepherd had not been a comics fan as a child, and he’d barely read a Phantom strip when he agreed to fly to New York as Frew’s advocate. He quickly became one of a small number of Phantom experts internationally, foremost among whom is probably Barry Stubbersfield, a dedicated Brisbane ‘phan’ who over the years has compiled an impressive trove of Phantom lore. Shepherd and Stubbersfield have put together the world’s only known encyclopaedia of Phantom trivia and publishing history.

Even as Australians have developed over recent decades a fashion consciousness which might have pacified Robin Boyd, even as our pubs are ‘done up’ and our dining has gone a la carte and our shopping malls are tiled white and our hair is designed and our brick frontages are rendered and our kitchens and bathrooms are renovated, there remains an inherent dagginess to the Australian character. We see it in trakkie-daks, in lazy beach days, in sporting crowds, in The Castle and Kath & Kim. Is it too harsh to describe The Phantom as the Daryl Somers of comic magazines? Frew has never been a stylish outfit, its dull newsprint covers remaining unchanged for its first forty years before Shepherd’s minor revolution, which ushered in unedited reprints, glossy wraparounds, introductory editorials, the odd larger edition and an occasional letters section. But the editorials are awkward, the graphic design amateur. Shepherd, a bit of a dag himself, until recently censored naked breasts drawn by Scandinavian artists when their stories were reprinted by Frew. Despite (or because of?) its inherent dag factor, The Phantom is among the minority of periodicals whose readership did not decline during the Global Financial Crisis.

With Shepherd’s passing, The Phantom’s future in Australia is perhaps uncertain. For now, his wife Judith, who has long worked as Frew’s senior editor, will keep the legend living. But it is worth pausing to reflect on Jim Shepherd’s role in bringing Australians their best-loved costumed superhero in a way that reflects something of the character of this place.