But Audrey is partial to the Panasonic birds, a cheaper but no less handsome variety; they acknowledge the dawn without extravagance, pip pip pip pip pip, little notes of fixed widths, such deft, even spacing. They are not meant to be here in the city; Audrey suspects they have migrated from Russet Hill, a network over a hundred kilometres away, renowned for wildflowers. The birds have a talent for evasion, as Audrey has never seen them at the reassignment plant; just as well, perhaps, for to crack open such a tender body, to see the inert parts that produce the sound of her dawn – it would surely be an act of violence. Audrey slips into the morning – or perhaps the morning slips into her, like a suggestion, pip pip pip pip pip – opens her eyes to a crisp blue sky, so bleeding-edged in its clarity. It is the kind of sky that reminds her that she was once loved.

The traffic is not so loud that she can’t discern the Citrus Man cycling down the street, the clicks of his wheels, the brittle music-box tune that pings from his gramophone. That old song – oranges and lemons say the bells of St Clement’s. She has never purchased fruit from the Citrus Man, but, as with so many things in this city, she cannot help but have affection for his presence, a belief in his importance: that not one part of this city is dispensable, not him, not the birds, not her, as she slides her legs into her overalls, fills the kettle with water, scoops black tea leaves from a battered tin.

Gently caffeinated, Audrey turns the locks of her apartment, exits briskly to the streets with their striped and creaking awnings, passes the buoyant results of the stock exchange. A man punches a code into an automated teller machine, removes the bright bills; a publican overturns barstools. Audrey can still hear the Citrus Man’s music box, camouflaged now by the eight-fifteen tram, the Coca-Cola birds, the queues shuffling through the bureaus and banks and offices, the shop bells ringing with their first customers of the day.

At the reassignment plant she punches her card and crosses the first floor, where workers disassemble birds and insects and amphibians so that the parts can be reassigned; they clean the cogs, bolts, circuits, screws; they sort them according to grade and size. No part is ever judged unfit to be repurposed. Someday the parts will be reincorporated into new wholes, inserted into new networks, sponsored by a different corporation; maybe the Panasonic birds to whom Audrey listens so keenly in the morning contain parts that once belonged to Coca-Cola birds.

Audrey ascends to the second floor, where mechanics like her collect their day’s allotment in closed wooden boxes. Before the animals are sent to the first floor for disassembly they are delivered here, their last chance to be repaired and reintegrated into their network. Mechanics receive a commission for each animal restored, though Audrey believes that there is some inherent reward in clipping the parts together, resetting the animal; some satisfaction to know that it thrives in some distant network once again conveying pollen, regurgitating nectar, lubricating soil.

Today Audrey opens her wooden box and finds it empty. She checks that it is indeed her box – it says AUDREY KWAI on the label – and opens the lid again. A cold memory revives itself. But then Cornelius the second-floor supervisor leans out of his office, his spectacles already lit with dust: Ah yes, Audrey – the return machine on Cambridge is out of order. Mind taking a look?

She did not always work at the reassignment plant: in another life she repaired ticket machines, all kinds, but mostly the ones at train stations, their buttons polished smooth by generations of hurried fingertips. She used to wonder if commuters appreciated the sound of a coin rolling through the slot, the rich clunks as it navigated the machine. A crisp new ticket, an unrepeatable date and time. In this other life, Audrey was a collector of tickets, everything from the theatre pass to Le Sacre du printemps, hole-punched by an indifferent usher, to the forked slip she pulled at the delicatessen counter, number 25. She liked transport tickets the best: their sharp corners, inkjet smell. Their typeface optimised for legibility, to be understood by tourists, locals, ticket inspectors alike.

It is because of this past life that Audrey now arrives at Cambridge Street with her toolbox. She has a letter of authorisation from Cornelius, but Audrey thinks she is unlikely to be questioned: a school, a church and silent apartments are all that comprise this corner of the city. Audrey has borrowed a broken Cadbury frog from the reassignment plant to test the machine. When she places the frog in the slot, the machine does not accept it. No numbers click the scales, no coins tumble from the chute.

Audrey pockets the frog. She loosens screws, opens the face of the machine, observes the maintenance sticker that says that the machine was inspected and emptied one month ago. A clutter of animals and animal parts has accumulated like irregular confectionery, not enough to cause a malfunction; nonetheless, Audrey unfolds a basket and empties the shaft.

Return machines are not at all like ticket machines – they are reverse vendors, the recipients of goods in the user–machine transaction, complicating the axis of trust. When Audrey repaired ticket machines, it was not uncommon for her to discover one or two counterfeit coins amongst the legitimate tender – slugs, were what her colleagues called them. Though ticket machines are adept at recognising slugs, swallowing the counterfeit and refusing to dispense a ticket, over her career Audrey amassed a sizeable collection of slugs in her toolbox, some nothing more than crude washers, others with an astonishing resemblance to their authentic counterpart, down to the grooves on the circumference. Sometimes, when Audrey is tasked with repairing an actual slug at the reassignment plant, she remembers that other kind, the slippery connotations of both.

There is a sound coming from Audrey’s basket, the slightest articulated tremors, rrrp, rrrp. Audrey carefully shifts dislocated heads and abdomens to find the source: a bee, legs flailing as if riding an upside-down bicycle, too small for Audrey to determine the sponsor. She supposes it belonged to a park in the city, for bees cannot fly far. She wonders how long it has been inside the machine, kicking and kicking. She extracts a pin from her toolbox, flips her magnifier over her eye. Inserts the pin inside the bee to deactivate it.

Her mechanic’s eye is always drawn to the wholest animals, hypothesising causes of malfunction, possible solutions. The sky is still blue, the street is still silent; somewhere in the city the Citrus Man still cycles, and Audrey’s most significant days are those that begin like this one, without portent, glowing with the kind of ordinariness on which she leans entirely. But today, her eyes fall upon a bird in the basket; as she lifts it from the pile, something in the universe pivots quietly, creaks imperceptibly, like the wheels turning in a cassette tape.

She has not seen this bird before. Her first suspicion is that it is, at long last, a Panasonic bird, but as she turns the body in her hands, she knows this is incorrect. She twists her magnifier and searches for the sponsor name – birds, the largest and most recognisable animals, always have a major sponsor – but there is no identification.

She turns the bird. No facet of its design suggests a manufacturer. Without opening the body she cannot ascertain what the bird’s network purpose was – to disperse seed, pollen; to monitor; to sing. Ten minutes pass before she realises that the bird has no activation pinhole.

Across the road, the school siren rings. Audrey looks up at the gaping machine, for a moment lost in its very insideness – the belts, pinions, coils. Bolted to the machine’s exterior is a sign that reminds citizens that it is a criminal offence to vandalise or steal from a return machine, and in the style of the train tickets she once collected so attentively, the sign is typeset plainly in capital letters, to be understood by tourists, locals, machine inspectors.

Still, it has to happen, on this empty street, on this unremarkable day – Audrey turns the bird a final time, wraps it in a handkerchief, and pushes it deep within her pocket.

Nobody knows what compels the animals to migrate, but also, nobody knows, truly knows, what it was that caused the original crisis. A disaster of first nature. The day that bees were falling out of the sky, suddenly turned flightless. Is it a real memory of Audrey’s – an infant at the time – this image of bees twitching on the ground in their thousands, their brittle, feeble buzzing, or did Audrey absorb the image much later from a schoolbook? Or is it, perhaps, that this is the memory passed down, made true through its insistent reproduction, a cultural heirloom?

Or could it be that, since the day that Audrey threw out her ticket collection – save one, a faded ticket for the river ferry, softened at the edges – something had happened to Audrey’s memory itself, a quiet transformation, heaving weakly to accommodate a vast and unimaginable trauma?

At home, after work, Audrey snaps on her desk lamp and unwraps the bird. It is not an ugly bird, but it resists comparison to the birds she fixes at the reassignment plant. As if someone studied a bird and replicated it from memory, with none of the inferiority one associates with replication; as if ‘bird’ was just a reference point, a figure from a dream.

Audrey angles the lamp, probes the exterior until she detects an interruption. The right tool and the body yields, halves asymmetrically, intimate as a dollhouse; there is something endearing about it, this private arrangement of parts. They all fit together, in an inexact way. Some of the connections are tenuous, and in fact Audrey sees that the bird is inoperable not because of a single fault but a number of parts that have worn away as a result of their imperfect tessellation. She cannot, still, discern the bird’s purpose.

There are hobbyists, she knows, who assemble animals, though the Department of Second Nature prohibits their activation in public. While this bird might well be a hobbyist’s work, Audrey finds the premise unconvincing: something in the humbleness of the arrangement, the absence of an activation pinhole. Audrey unearths a yellowed pad of graph paper and a pencil, transposes the bird onto these squares, numbering the parts; tenderly, she dismantles the bird and soaks the pieces in white vinegar. Across the night, through her quiet window, it is time for stray frogs to open their throats. Samsung, Toshiba, Cadbury; their creaking dialogue, all the tongues of industry.

Again, the Panasonic birds; again, the Citrus Man; again, the reassignment plant. This time, Audrey’s wooden box contains a series of silkworms. All morning she has replaced spools, tested salivary glands; at ten o’clock, Cornelius approaches her workbench, asks if she might know why the weight of the animal parts did not match the reading on the return machine from yesterday. A discrepancy of about sixty grams, he says; she responds that the scales had malfunctioned, and as Cornelius nods, scribes on his clipboard, she admires the ease of the lie, gliding like a gear with perfect teeth. She returns to her silkworms, sends the inoperables down the chute.

The diagram of the bird is folded in her bib pocket. During breaktime she studies it in a restroom cubicle, commits the dimensions of the required parts to memory, returns to the plant floor and slips candidates into her pocket. Yesterday’s chill of opening her empty wooden box still hovers – somewhere, a ticket machine explodes quietly, not so deep in the past that its reverberations can’t disturb the present.

After the silkworms, a wasp. After the wasp, a moth. Through the window, the sky is an imitation of yesterday’s, an unsatisfactory facsimile, like a perfume sample in a magazine.

How distant, that blue sky – how faintly persistent – under which Audrey once stood, holding a boy’s hand on the river ferry. The world was bright and forgiving then; time was worth marking with tickets. She remembers how the dragonflies floated like helicopters, kissed the reeds at right-angles. That day, she didn’t know that those particular reeds are pollinated by the wind, not by insects, so the dragonflies must have migrated from another network; but, whatever their origin, they were witnesses to her short-lived good fortune; she was, to someone’s eye, indispensable.

She can still detect it, that facsimiled sky – turning mauve now – as she walks home from the reassignment plant, rotating a stolen cog in her pocket. The diagram of the bird creases against her chest every time she breathes. Cornelius had smiled at her as she clocked out and it pains her, his simple trust, the papercut sting of it.

She is relieved when the sky exhausts its colour, and the ferry is small on her memory’s horizon.

She notices, then, the broken window of her apartment. A single, decisive puncture. At first she thinks it is a trick of the light, ghostly as an autostereogram, but it refuses to be blinked away. Audrey grips the cog in her pocket, slides it between her fingers. She climbs the stairs two at a time. The arrival takes forever.

Turning the locks, bursting over the threshold, to her desk – the toppled beaker of vinegar, rocking in the intruding breeze. Shipwrecked on the liquid surface: two bolts, a screw, a pair of tweezers. Parts have been dragged through the spilled vinegar, spiking the puddle’s edges; she can even perceive a trail of pronged footprints, determined as arrows. And the bird, which she had left open on the bench, is gone.

Audrey’s hand moves over her heart, to her bib pocket, expecting the diagram, too, to have vanished; she flounders to extract it, confirms: the bird was here – then scrunches this tangible memory along the wrong folds, clutches it to her chest like a mourner’s handkerchief, while the cold afternoon hurtles through the window’s wound.

Before he left, he had the nerve to ask her to exchange some notes for coins, so he could purchase a train ticket to the city where the other woman lived. A thorn which sunk deep, piercing some vindictive vein Audrey did not realise she possessed. She performed this favour anyway, and on that last morning handed him a ziplock bag of coins, buffed to a deceptive shine: slugs, all of them.

It was not meant to have consequences, this feeble revenge; she supposed it would take not more than two attempts before he realised. When the slug rolled through the slot nothing was meant to happen, absolutely nothing, but it was as if the machine was animated by her indignity, summoned to act beyond its regular function; the explosion sent unprinted tickets pummelling through the air, coins flashing – that’s what the witnesses remembered the most, coins strewn like dying bees, although Audrey also heard about the young man thrown off his feet, the blast propelling, with malevolent accuracy, a slug into his temple, a shard of which remains lodged in his skull to this day.

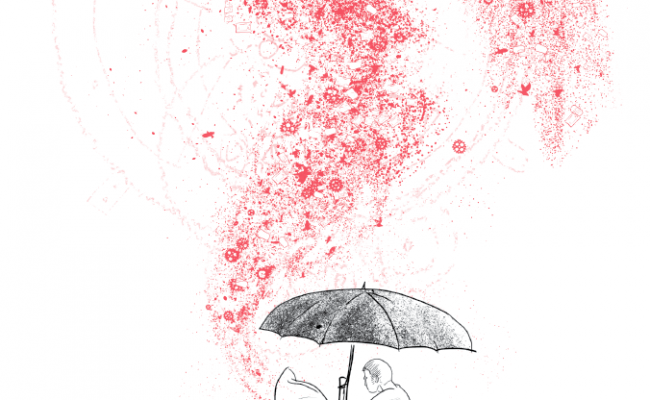

The investigation labelled the event a freak accident, but she resigned all the same, fearing the day when she’d be cut loose. Ticket machines are not supposed to explode. But Audrey wonders if machines are themselves part of second nature, if they are categorically the same as the birds and insects that toil away in their networks – all of them lively, wilful, migrating out of turn; enacting, in their quiet malfunctions, an unauthorised evolution.

Sometimes, Audrey gets the notion that there is nothing outside the city, no farms, no fields, no vast harmonious networks. In this vision, the animals that the mechanics repair and ship out of the city are all redirected to one factory, where an assembly line opens the animals, roughens the parts, ships them back; some parts are scattered in parks and thoroughfares for unwitting citizens to pick up, redeem for coins at return machines; the only real things are the sponsors, the benefactors of this operation, while the stock exchange results are algorithmic fabrications of the Department of Second Nature. But then Audrey thinks: where does the honey come from, the fresh flowers, the vegetables and fruit? – and the vision disappears, but not wholly.

Audrey, woken on this new morning not by the Coca-Cola birds, nor the Panasonic birds, but by the whistling of the broken window, a disruption to her routine waking. She listens for the Panasonic birds, receives their pip pip pip pip pip with the scantest relief; listens ever more keenly now, desiring the city’s wholeness – there, the Citrus Man, oranges and lemons say the bells of St Clement’s. The air is still soured by vinegar; she has not swept the glass, and for all her expertise Audrey cannot discern whether the hole was made by something exiting or entering. She had fallen asleep with the lamp on, and her fingers still grasp two things: one, her river ferry ticket, her last mark of time; two, the pencil diagram, the vanished bird.

Pip pip pip pip pip – Audrey, overwhelmed by the liveliness of objects, holds the ticket to the light, against yet another crisp sky, relentlessly blue. Sometimes it seems that everything in this city conspires to remind Audrey of her impermanence and obsolescence, from the blue sky to this smallest ticket, inkjet-fragrant, words still legible despite the intervening years. It’s some kind of amazing, the things that outlast us.