In August last year, the NTEU reported that two in three people employed by Australian universities do not have secure employment. In other words, over half the work conducted in universities is undertaken by employees who do not have an ongoing contract. Of these workers, 43% are employed on a casual basis, while 22% are engaged on a fixed-term contract. To put it in perspective, only one-third of university staff have secure employment, while three in four Australian employees enjoy the benefits of secure work and entitlements.

Therefore, if you or someone you know works at a university, your job, or their job, is most likely precarious. Moreover, if you’re a casual academic, you’re just as likely to attain a contract as you would be if you worked at McDonald’s. Their secure employment rate is 21%. At Monash University, one of the worst providers of secure work in Victoria, the secure employment rate is 27%. Working at an Australian university is just as precarious as working at Mickey D’s. Except there the parking is free and you get a toy with your lunch. Sometimes, the Wi-Fi is better, too.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, precarious is an adjective that means ‘in a dangerous state because of not being safe or held firmly in place.’ If something is precarious, it is unstable or under threat. A precarious job is one that is insecure, subject to change (and chance), and dependent on circumstances outside of one’s control. A precarious situation is likely to get worse before it gets better. Let’s use it in a sentence: ‘Most people do not enjoy precarious work.’

If you’re a casual academic, you are an expert first of all in precarity.

You know, for example, that there is no such thing as ‘casual’ work. You prefer the oxymorons ‘permanent casual’ or ‘long-term casual’ because, like many of your colleagues, you’ve been working full-time hours for years now – just without the benefits.

As a casual, you have no annual leave, no holiday leave, no research leave, no carer’s leave, no domestic violence leave, and – less critically, since you’re never unwell – no sick leave. You don’t have access to funding for conference fees or travel, or any form of professional development. There’s no remuneration for designing and re-designing teaching materials and curricula; no compensation for attending meetings, organising readings, digitalising resources, peer-reviewing articles, replying to e-mails, or hosting negotiations with Jenny from Payroll.

You’re not reimbursed for mentoring undergrads, supervising projects, reviewing coursework, editing grants and proposals, or promoting your faculty during O-Week. And you can forget those long, drawn-out hours spent on cross-marking and double marking and moderating. You don’t even have access to the photocopier. At the end of semester, when your e-mail account is deactivated, you will no longer be able to borrow books from the library and the swipe access to your office will expire. And by office, we mean the kitchenette where your hot-desk is located, when the space is free.

So, what do you do?

First of all, you don’t complain. You earned this job through months of unpaid labour, years of study, and the gradual accumulation of a life-long debt. However, the honour of a casual appointment is bestowed upon you, and later stripped away from you, in a popularity contest judged at the discretion of a unit coordinator.

To be given casual work is a gift.

And – to expand on the Maccas metaphor – a lot of people want to eat at this restaurant. In fact, there’s a queue behind you, and this queue is long. As you’ve noticed, it takes some time to get ahead. When you do finally reach the front counter, you must conduct your business quickly and without fuss. For the sake of everyone, you must not complain. The people in this queue are just as hungry as you, and just as desperate. Some of them are sure that they’ve been waiting longer than you. Others are smarter: they’ve beaten the crowd and ordered ahead. Others are smarter yet: they have a friend behind the counter. Everyone wants their Happy Meal and the toy they’ve been promised before it sells out. More importantly, no one wants to stand in a queue where – through some strange combination of faculty restructures and budget cuts – you can never get ahead.

No one chooses to be casual.

Saying ‘yes’ to a casual job is not really a choice when your choices are: casual job or no job at all.

Choosing between a bad option and a worse option – as we see time and again in politics – is a contextual dilemma: one that reflects the unavailability of better options and more effective forms of objection, and one that, by extension, poses serious questions about the assumption that freedom of choice is synonymous with freedom itself.

So, imagine your surprise when last month The Conversation published an article about the ‘benefits’ and ‘challenges’ of casualisation in academia.

Let’s start with the benefits.

According to the article’s authors – three senior academics who are presumably tenured – many casuals ‘enjoy the flexibility of working across different institutions.’ These mystery people should reveal themselves because the authors of this article are extremely interested in meeting them.

Working across multiple universities – what has affectionately been dubbed ‘taxi-cab teaching’ – is the equivalent of holding down several jobs just to pay your rent. Except, if you’re a casual, you won’t be catching a cab to work because you don’t have a fare allowance. Or any allowance, in fact.

If you’re a casual, you work multiple overlapping contracts at different universities because you need to eat, and unfortunately, the hours that you’re paid at Uni A are not enough to cover your groceries for the week, nor is the wage you receive at Uni B. So, you work at Unis A, B, and C, because you need food and shelter and running water. And you sleep under your desk at Uni C because you can’t afford your rent. You don’t sleep there because you love ‘the flexibility’.

In fact, the Workplace Gender Equality Agency does not consider casual work to be flexible at all: ‘flexible work’ means that you have adjustable work hours and access to paid leave. As a casual, you take whatever you can in order to pay your bills, especially during the many weeks of the year – often as many as twenty-two – when you have no income at all.

Let’s not confuse flexible work with poverty and functional homelessness.

Let’s also remember that if you work at different universities, you have multiple supervisors to report to, different institutional policies and expectations to uphold, and various pay dates and cut-offs to remember if you want to get paid.

Your classes might be scheduled on the same day, and the campuses that you work at might be located not minutes but hours apart. On those long drives in peak-hour traffic, you won’t be reimbursed for the petrol you use or the hundreds of kilometres that you clock. You won’t be able to claim your trip between home and work because the ATO says this kind of travel is ‘private’. When your back aches from driving, and you’ve just filled up your tank for the third time this week, or you’ve missed the last bus home and can’t afford an Uber, you won’t be thinking how much you enjoy your job. You won’t be thinking, ‘Wow, it’s so flexible!’. You’ll be using another word that starts with f.

But that’s okay because, according to The Conversation, there are other advantages of casual work. For example, as casuals, we ‘don’t have to fulfill service requirements, such as attending meetings or annual performance reviews.’

Actually, we do go to a number of meetings, not always voluntarily and, again, usually without getting paid. Sometimes, for example, a well-meaning supervisor will ask us to stay back for a ‘quick catch-up’ that inevitably lasts an entire afternoon. Other times, we meet with students after class because they don’t understand the assessment the lecturer has set.

It’s true that we aren’t invited to department meetings or staff meetings, and our colleagues are quick to remind us of our good fortune in this respect. ‘You’re lucky you don’t have to attend,’ they laugh. But here’s the kicker: most of us would like to attend meetings in which decisions are made about our workloads, the courses we teach, and the training we receive. Most of us would like to be included in the decisions that affect us. And since we do more than half of all undergraduate teaching, and teaching brings in more revenue than research and consultancy combined, we should have a seat at the table. In fact, as the lowest-paid academics who bring in the most money, we should have the table. And an office space! And staff profiles, too!

Yet career-development programmes that are designed to help casuals transition into permanent employment have been cut, at the same time as face-to-face classes are being replaced with online content. Casuals are paid minimal preparation time for a class, and what usually equates to only twenty minutes per student for an entire semester of marking and moderation. If your class is overloaded, your adjusted hourly rate will be less than the minimum wage.

If we don’t have job security and enough money to support ourselves, then our non-compulsory attendance of meetings is an exclusionary device, a way to keep us powerless and on the fringes, a mechanism to keep us quiet while our labour – the wealth generated from the services that we provide – is dispersed into marketing, bonuses for management, and unnecessary infrastructure.

Students subsidise infrastructure and research as part of their tuition fees. A 2017 report by the productivity commission claims that tuition fees generate a ‘teaching surplus’ of $1.5 billion. At the same time, managers carve out bonuses for lowering the cost of running courses, essentially pinching the very funds that casuals and students bring in, all the while claiming that there isn’t enough in the budget to pay for extra marking or sick leave or professional development. But we’re not the only ones ripped off when teaching is underfunded: our working conditions are our students’ learning conditions too.

In the United Kingdom, the National Audit Office reports that students are feeling ripped-off, largely because they sense neglect in terms of where the cash is spent, which is not in their classroom, though the room itself might be very flash. In this gig economy – a cycle of exploitation that outsources the most important work, and which is based primarily on profit maximisation – it is not only us who suffer. It is our students too, and they are starting to catch on.

In 2017, the Human Rights Commission on sexual assault and harassment in Australian universities found that constant staff turnover means that students cannot build relationships with their teachers. Arming casual academics with adequate training in pastoral care – including how to respond appropriately to reports and disclosures of sexual assault – is difficult when staff aren’t paid for training or, worse, are excluded from education programmes altogether. As a result, sexual assault goes unreported because trusted teachers who work on the frontline keep disappearing, and students and even staff may experience vicarious trauma. Poor training, combined with a high employee turnover, only creates additional barriers to reporting, which means that the most vulnerable students are lost in the most insidious of ways.

Naturally, general morale and wellbeing is affected. But still, the benefits! The flexibility!

According to the article, another benefit of casualisation is that casual staff have ‘high levels of commitment’ and ‘regularly go beyond their contractual obligations.’

Of course, this is true. Two-thirds of staff carrying out unpaid work is a huge money-saver for an institution.

As casuals, we aren’t paid to meet with students or to engage with them online. We aren’t paid to enter grades or remark papers. We don’t have workload points or a special allowance for service. We aren’t paid to publish, even though universities will happily claim links to our research by virtue of our notional working relationship with them.

So, why do we do it?

Initially, we work for free because we believe the lies we’re told. That it’s a good experience. That it will look great on your CV.

At some point, we see through that. And yet, even then, we continue to slog away. We continue to work freely and voluntarily, in our own time and at our own expense, because we’re passionate about our work and committed to those values that universities claim to espouse: innovation, progressive thinking, opportunity for all.

We care about our students and their work. We don’t want them to drop out. We understand what it’s like to feel anxious, unsettled, and unsure about the future. We remember wanting to belong at university, and in the process, not realising that our teachers are just clinging on too. We know what it means to be in a precarious position.

Why suggest that casual work is ‘something of a double-edged sword’ when our experience doesn’t cut both ways?

The very title of article is offensive: ‘Casual academics aren’t going anywhere, so what can universities do to ensure learning isn’t affected?’

The presumption here is that casual academics have nowhere else to go – that beyond the university, we’re unemployable. Even though our work security is dependent on the same qualifications that permanent staff have attained, our value is dismissed. And here is where that idea of casual work as a ‘gift’ germinates. If management really believe that their own graduates, holding their own qualifications, have nowhere else to go, then perhaps they should be considering the ethics of manufacturing those degrees and selling them. Or else we’re all working in what the NTEU calls a McUniversity. And no one, it seems, is lovin’ it.

Perhaps this is why a new genre of journalism, quit lit, has formed around the testimony of ex-academics, producing sometimes hopeful articles about life after academia.

Ultimately, what the Conversation contributors fail to communicate is that casualisation is not a valid hiring practice with ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ but a system of exploitation that brutalises academics and imperils not only teaching and research, but the spirit of inquiry itself.

The closest the article comes to acknowledging this is the lone comment that ‘casual academic contracts have none of the benefits of continuing contracts.’ Yet the insensitive and misleading assumptions that the authors perpetuate undermine any real sense of understanding or empathy for those who are stuck without a viable path to a secure future – or even know if they’ll have work next semester.

Granted, the article claims to advocate for university administration to manage their casual staff ‘more effectively and equitably’, and to offer more permanent positions. At the same time, however, the authors suggest that casual staff ‘pose risks’ to student satisfaction and to the quality of their learning experience.

This myth vilifies the very people who work at the interface between students and the university, and who play a significant role in improving participation and retention. Also, let’s not forget that our work doesn’t go unchecked. Each semester, we’re subject to a number of surveys, designed by a centralised ‘quality manager’ and completed by students. These surveys aren’t so deadly when you’re permanent and teaching is only one component of your paid workload. As for casuals, however, no one has to fire us or explain what we did wrong: they just don’t invite us back.

Instead of engaging in a serious conversation about the problems of casualisation – instead of asking why it is that casuals academics ‘aren’t going anywhere’ or why reducing reliance on a casual workforce should be a priority of university leaders – the authors fixate on casuals themselves as the problem. Instead of identifying or even acknowledging the different types of casuals who comprise the academic underclass, they heap career casuals, industry casuals, and PhD-candidate-casuals together.

In doing so, the authors elide the systematic brutality that casuals experience every day.

If the tables were turned, how would permanent staff cope with the two-thirds of teaching now in their hands? Would they miss the burden of safety that comes with a contract? Would they enjoy the flexibility? The article’s title accepts – therefore absolves university management for – institutionalising casualisation. Yet all forms of exploitation have benefits for some.

Perhaps even more problematic than the publication of this dangerous and misguided article is The Conversation’s response to its reception. In response to the backlash on Twitter and the push by several academics for a right of reply, the editors cited their ‘no response’ policy and encouraged readers to reply to the article in the comments section instead: a move that seems at odds with the publication’s mandate, which is – as their name suggests – to facilitate conversation and debate. Perhaps they could start by finding ways to pay their casual academic contributors since, as we have already pointed out, casual teachers aren’t paid to publish. Having any conversation, for us, means more unpaid labour.

The Conversation – which has the audacity to ask its unpaid contributors for donations – claims to ‘set the standard in journalism best practice’. Yet its ‘no payments’ policy skews it towards tenured academics, making it a very narrow representation of academia. If The Conversation so venerates research expertise and judgment, then a stronger sense of research ethics needs to be reflected in their charter, especially with regard to protecting contributors and reducing harm for authors and subjects alike. Some recognition of the precarious working conditions of potential contributors would also be welcome.

Casual academics are not the problem. The inequalities facing students are equal to those of their teachers. If universities are to deliver quality education to their students, as well as foster a thriving research community, then research and teaching need to be intimately paired and supported, starting with awarding ongoing contracts to casuals. Advocating for better working conditions is the only way forward. The system pits casuals against each other. One casual can’t effectively object on their own, from within the queue. But as the largest group of teachers in universities, casual academics are certainly powerful enough to ask for what they need when they are united.

Not only is creating more ongoing contracts and better conditions for casuals a smart business move if universities are to retain their biggest revenue generators, but it is the only ethical way forward.

Management at all levels should be asking themselves: what is a university?

Is it a place where academic freedom, diversity, and progressive education create intelligent and engaged citizens? Or is it a place primarily of enterprise: one that strives for profitability and efficiency above all? Do we support our teachers or do we exploit them? Do we make citizens out of students or do we make shareholders out of customers? Do we want to lead by example and foster a fair and inclusive peer-led academy? Or should we be teaching our students early that the market is competitive and that you’re only as valuable as what employers can get away with paying you?

Finally, university management should remember who pays their bills, and every now and then it wouldn’t hurt to include with the invoice a simple thank you.

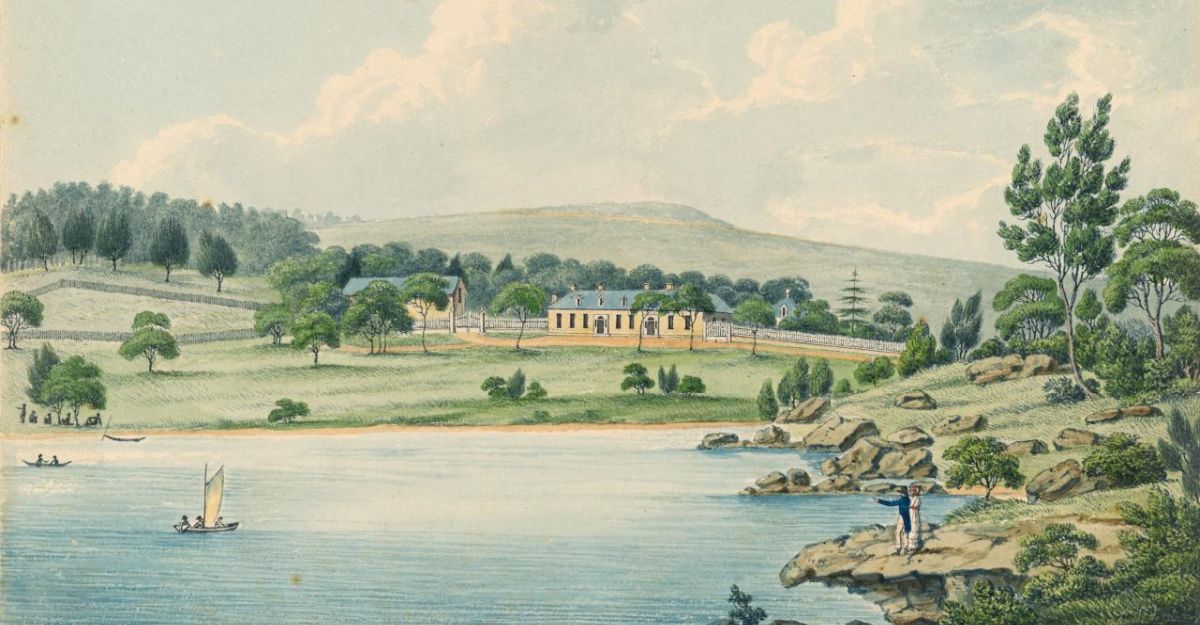

Image: Inside the University of Sydney Quadrangle, Flickr