It will take a while before we can draw definitive conclusions about what happened in America yesterday. Clearly race has been a major demographic issue in how people voted, as has geography. Plenty of ink will be spilled on these topics, but for now, I want to focus on the politics of gender.

One conclusion we can draw from recent commentary is that mainstream feminist politics has some soul-searching to do. Many feminist writers shifted their politics to the right by supporting Clinton. Rather than discussing the failings of a structure that rules for the wealthy and political elite, they argued that integrating a woman into this structure represented feminist progress. Many effectively sided with power over people.

The idea, we were repeatedly told, was that a woman in power was an important goal for feminism, that her success would represent a victory over misogyny. Laurie Penny made a rather confused case for Clinton with a disgraceful and unhelpful accusation of sexism towards people who drew a moral equivalence between the two candidates. Jessica Valenti dismissed accusations about the way she seemingly collaborated with the Clinton campaign to marginalise Bernie Sanders, a candidate who arguably would have had a better chance at beating Trump. Van Badham hit a rather notorious low point in her shilling. Jill Filopovic at one point claimed rather curiously that Trump offered dislocated white men ‘trade policies’ (among other things) as a convenient scapegoat. There were many, many examples along the lines that Clinton was highly qualified for the role, and that the rejection of this truth was manifest sexism.

This pitch, frankly, is like arguing that the fox should be in charge of the hen house because the fox has shown a lifelong commitment to chickens. The American people remained unconvinced that Clinton’s experience entitled her to their vote. No doubt some of this sentiment was garden-variety sexism. But much of it came down to the fact that Clinton was selling the status quo at a time when people were looking for change. As the New York Times described it, the Podesta emails revealed – alarmingly – that the campaign struggled to identify a core rationale for her candidacy. Her strong background in foreign affairs confirmed for many that Clinton was the candidate of the war machine. People remained unconvinced that what would essentially be a third Obama term would do much to alter inequality. President Obama presided over a redistribution of wealth away from the poor in the wake of the 2008 crisis, and the country now suffers under record levels of poverty. Around half of Americans earn under $29,000. Policies that affect poverty, like trade, are not scapegoats. They are legitimate grievances with the system and they underpin a desire for change that Clinton failed to address in her campaign.

She was the wrong candidate for this election. But unfortunately, the all-too-predictable outcome is that rather than examining the failings of Clinton-style feminism, the instinct has been to punch Left. Laurie Penny basically thinks that democracy can’t deliver truth (whose truth exactly? It remains unclear). Clementine Ford’s knee-jerk response was an attempt to blame Jill Stein voters for Clinton’s failings, on the basis of zero evidence. This is especially galling given Stein is also a woman (with more progressive politics than Clinton) and white women were an important demographic for Trump’s success.

It would be an enormous mistake to explain everything through the lens of sexism. The job of feminist activists around the world has to be to think carefully about how the politics of gender played out in this campaign. Sexism did play its part in the rejection of Clinton. Yet many women did not see themselves as aligned to her on the basis of sharing a gender. Gender oppression is only one part of this story. Simplistic analyses that see men as the problem – for which the binary solution is women – have led to a dead end. It’s time for something new. Or as the great Louise Michel summarised it nearly 150 years ago: ‘[a woman] bends under mortification; in her home her burdens crush her. Man wants to keep her that way, to be sure that she will never encroach upon his function or his titles. Gentlemen, we do not want either your functions or your titles’.

It might not feel like it right now, but there is a lot more to politics than elections. As Marx put it: ‘the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie’. There are dangers in spending too much energy singularly pondering how to better stack out this committee, when it is really stacked against us. It is also critical to remember that in some senses, America is not that different to the place it was yesterday – a swing of one per cent in a couple of key states would have transformed the results. Turnout was down for this election compared to 2012 and 2008, and was particularly bad for Clinton, while the Republican vote was pretty steady in absolute numbers.* That’s not to say this result was uplifting, more that the necessary work has always been to build a Left alternative to the status quo, and that this work has just become more urgent. The solution is not more technocratic tinkering. The solution is more democracy: more power for people to make decisions about their own lives, rather than promises of change that can’t be delivered.

Feminism, if it is to have a meaningful and promising future, must prioritise the politics of class and race over the politics of gender assimilation into the structures of power. Policies like the $15 minimum wage, free college education and universal healthcare (including reproductive healthcare) are central to fighting for women and especially for those who are poor and for women of colour. Paid parental leave, including polices that prioritise the sharing of childcare between parents, is critical. Free (or even affordable) childcare and early education for children is an achievable and necessary goal. Feminists need to make these demands openly and without compromise and to build movements in collaboration with other activists from the ground up to win people to them.

There is hope. Young people rejected Trump, for example, and they also overwhelmingly supported Sanders in the primaries. And many, many more people rejected the idea of voting altogether, suggesting that the electorate may well be open to a much more radical platform of social change and economic redistribution than Clinton’s sometimes tepid platform suggested. Indeed, there is little other choice than to work hard in order to test this theory out.

The system is broken, but through the cracks we can see space, hopefully even light. Bright and bold ideas have never been so important and may in fact have more potency in a time when people want change. Make no mistake: the ascendancy of Trump is a dangerous and backward phenomenon, not least because his slick victory speech indicated a potential shift from buffoonish renegade to confident lieutenant of capital. But for all of his populist posturing Trump cannot deliver the change that people want. It is the job of activists and ordinary people to forge another world.

*With rough calculations, using this for the popular vote and this for the turnout, I found that as a proportion of eligible voters in 2012, 41.4 per cent didn’t vote, 29.6 per cent (65.9m) voted for Obama, 27.4 per cent (60.9m) voted for Romney. In 2016, 44.4 per cent didn’t vote, 25.8 per cent (59.7m) voted Clinton, 25.7 per cent (59.5m) voted for Trump.

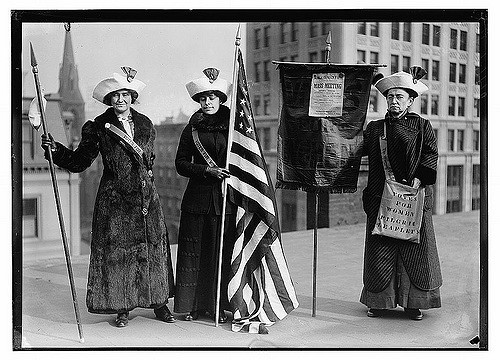

Image: ‘Suffragettes with flag’ / The Library of Congress