In 1908, Muslim camel drivers from Central Asia shut down the road from Port Hedland to the Pilbara goldfields for more than a week. They blocked the road, scattered their camels into the desert and waited for their demands for fair rates to be met.

The Western Australian press reacted in a familiar way, with panic about Muslim migrants and lawless strikers, which read like articles from today’s Daily Telegraph. Media, police and scabs were mobilised to put the camel drivers in their place and to ensure the flow of commodity capitalism would continue. Business groups met in Fremantle to discuss how to crush the strikers even as white wage workers reportedly joined in the blockade.

‘We were crushed down through these erroneous reports, and compelled to submit,’ one camel driver wrote over a year later, ‘[but] we had the sympathy of the working class almost to a man.’

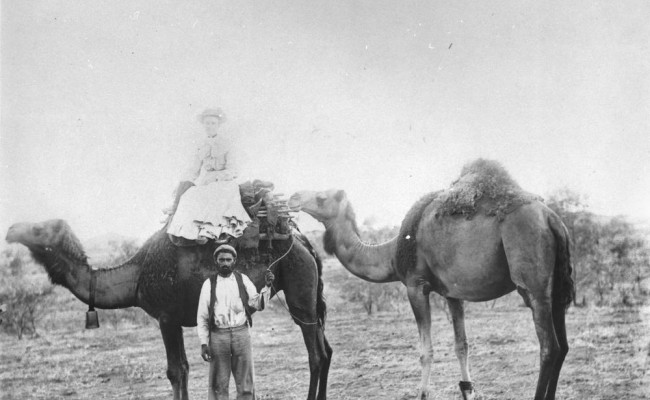

It was a dramatic confrontation of working people against capital and the state – one that continues to be ignored by the traditions of labour and radical history in Australia. Yet it’s a moment that the Left here should consider. Today, the history of the cameleers (or ‘Afghans’ as they were known then, though they came from an area that stretched from Afghanistan to what is now the most north-western part of India) is mostly used as a liberal lesson about multiculturalism. That is, the cameleers’ contribution to the federation’s economy becomes the premise for an enlarged, more inclusive nationalism.

Most recently, we saw this in Peter Drew’s ‘Aussie’ poster campaign, which depicted Monga Khan as a turbaned and moustachioed ‘Aussie’ with a history in this country of at least a century. Yet this message elides the conflict and contestation the camel drivers evoked at the time and the difficult position they found themselves in: Australia was a class-divided society coming to grips with its nascent nationalism and integration into the world market.

These cameleers came to Australia often on fixed contracts, many for only one to two years. Some stayed on, but the majority returned to parts of the British Raj or continued elsewhere. In Australia they were often in direct competition with white bullock teams in inland mining towns, who tended to secure the majority of the work. The cameleers faced discriminatory taxes and the condemnation of the Australian labour press. The media often argued for their exclusion and further immigration restrictions, employing both cultural and economic arguments that are familiar today.

White Australia’s rhetoric about ‘cheap coloured labour’ has obscured the history of struggle among the country’s migrant workers. Camel drivers from the recently pacified corner of the British Empire built unions in the Pilbara, the Esperance Goldfields and at Broken Hill – either on their own or in shaky alliance with white unionists who were forced to confront the conflict between their rhetoric on White Australia and the reality of building workers’ power on the ground. The issue of Afghan unionists and interracial organising became so contentious in the labour movement that the ALP’s first prime minister, Andrew Fisher, was forced to comment on the matter (he stuck to the party line on non-white migration, though stopped short of condemning the Broken Hill Branch of the Australian Carriers’ Union, with whom the Afghans were organising).

Of course, the Afghan cameleers were not united in their views on their temporary home in a new corner of the empire. Some appealed to the notions of British liberal rhetoric to be treated as equals amongst the queen’s subjects, some raged against the violence of imperialism and the chauvinism of Australian culture. The majority worked their time here without leaving a voice for posterity. We might try and fit them in as among the cast of peoples who first coalesced into ‘Aussies’, but they are also among the first migrants to experience exclusion and vilification from this newly consolidating national identity.

Just as this temporary migrant workforce was integral to the production of Australia’s key export commodities one hundred years ago, our whole system of food production today is based on a migrant workforce. There are the people who pick our fruit and vegetables for less than minimum wage: a combination of recent migrants from Southeast Asia building a permanent life here, so-called ‘working holiday’ visa holders here for a year or two from Taiwan and Hong Kong, Pacific Islanders here on a seasonal worker program funded through Australia’s aid budget, and those with no work rights whose vulnerability leaves them at the bottom of the heap. There are the massive Coles and Woolworths distribution centres, largely staffed by New Zealand citizens whose special immigration status lets them work as long as they want but gives no pathway to Australian political rights or social safety nets. Without these workers the shelves of grocery stores would be empty. In other words, our society’s very capacity to meet its metabolic needs and replenish itself would be in question.

Rather than appeal to the mythology of the ‘Aussie’, we must confront the inevitable logic of capitalism – that is, capitalism will always depend on the international flows of people to produce profit. The erection of modern border regimes in the nineteenth and early twentieth century did not limit booming international markets any more than the creation of the Australian Border Force interrupts what we term ‘globalisation’. Instead, immigration controls function to categorise people and limit their rights so as to better fulfil their economic function.

The camel drivers who blockaded the road from Port Hedland were instrumental in the economic development of Australia. They left a lasting legacy in the white and Aboriginal communities in which they resided. But let us acknowledge how contentious their presence was. That way they can be remembered not simply for their part in nation building, but also in Australia’s history of labour struggle and radical dissent. They can help us to acknowledge how deep the roots of today’s xenophobia and exploitation run.

If you’re interested in the ideas raised in this article, consider entering our Fair Australia Prize, open until 31 August. There are $4000 prizes for fiction, essay, poetry and cartoon/graphic that explore the theme ‘our common future’. Read more.

Note: an earlier version of this article referred to Monga Khan as a cameleer, but this claim has since been disproven.

–