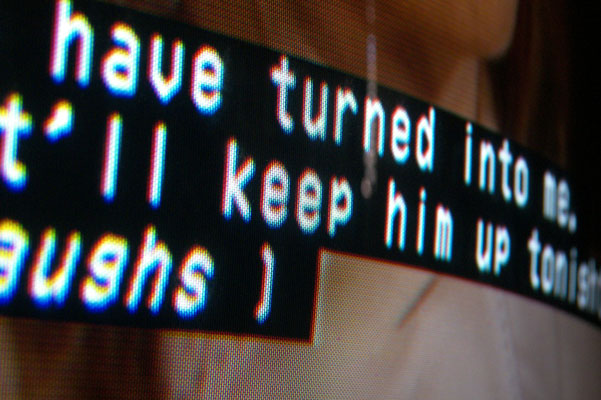

When I told people I’d started working in the live department of a closed captioning company, they’d ask what the job actually involved. Then they’d say something like, ‘Some of those captions are terrible. The other day I was watching the footy at the pub, and I saw one that said [insert egregiously unintelligible sentence here].’

Having grown up with several deaf and hearing-impaired family members of varying ages and interests, I was accustomed to watching television with the captions on – so I was also accustomed to their often dismal standard. Sometimes they’re incomprehensible. Sometimes they’re delayed. Sometimes they obscure important graphic information on the screen. Sometimes they’re absent.

So while I’m not reliant on closed captioning, I’m well aware of its foibles. But I also know it requires enormous amounts of speed, concentration and accuracy, and it’s very easy to mess up. It’s a weird job that requires some explanation. Here’s how it works for live-to-air material.

A captioner sits watching and listening to the studio feed from the television network. The captioner is either a stenographer or a respeaker. Stenographers use a machine, much like a little typewriter in appearance, which they’ve trained with their personal shorthand – maybe ‘Bjp’ for ‘Bjelke-Peterson’, for instance.

Respeakers, on the other hand, verbally repeat what they hear, including punctuation and other grammatical conventions, into a microphone. Verbatim, a typical sentence might resemble something like, ‘Yeah comma thanks comma mate full stop it was a good match and I am proud of the boys plu-pos performance full stop.’ This audio is then relayed to voice recognition software, which, in turn, produces the captions. Here, the respeaker is undertaking several separate but related cognitive processes simultaneously: listening, editing and repeating (as well as occasionally fiddling around with temperamental technology).

Perhaps most obvious are the mistakes known as ‘misrecognitions’. ‘Hawthorn’ appearing as ‘core porn’. ‘Election booths’ appearing as ‘election boobs’. ‘Sergei Lavrov’ appearing as ‘Sir gay lover of’. (I own all of these.) This can happen because the words don’t exist in the dictionary of the speech recognition software – that is, its vocabulary. You have to teach it a lot of proper nouns, neologisms, foreign words and other stuff. This involves tonelessly repeating ‘Kyrgios. Kyrgios. Kyrgios’ into a microphone and waiting for the software to recognise it.

Mistakes can also occur because of unclear speech input. Speaking the way that voice recognition programs require involves heavy concentration on tone, emphasis and enunciation, and each respeaker has their own highly individual voice profile allowing for different accents and cadences. Even a head cold can drastically affect accuracy.

Sometimes – and most frustratingly – the software can be glitchy. You’ve said ‘Abuja’ dozens of times before without a problem, but one day the computer refuses to recognise it, and spits out some nonsense syllables instead.

And sometimes you have to wing it. This captioner for Ai-Media describes preparing to caption a live-to-air cricket match, only to have the scheduled game cancelled due to rain and replaced by a replay of a 1981 match between Sri Lanka and the West Indies. Not only was the captioner missing all relevant information – names of players and coaches, for instance – but voice recognition software tends to struggle with foreign-sounding words and phrases at the best of times, meaning it is unfortunately much more likely to approximate ‘Mitchell Johnson’ than it is ‘Kumar Sangakarra’. Likewise, breaking news doesn’t always allow for adequate preparation time. Here, it’s important to make the distinction between pre-recorded or ‘offline’ programmes, which typically allow for high accuracy, and live or ‘online’ programmes. (The Deafness Forum offers a good explanation of the difference between these.)

None of this is intended as an excuse; the point is that there are dozens of reasons why the end product can fall short. These are compounded by the fact that captioning is a business: several companies compete for each television network’s contract, which increases pressure on the captioning companies to cut costs where possible. Quality is sometimes a casualty. It doesn’t help that there are no nationally recognised standards for captions, although Media Access Australia does provide a set of general guidelines.

Things are getting better. Feedback from viewers who actually rely on captioning is generally positive, and often it comes at unexpected times – following the live coverage of the Martin Place siege, for example. Last year, Yahoo7 was the first commercial catch-up TV service to provide captions. Theatre performances and public events –from musicals such as The Lion King and Dirty Dancing to selected program events at the Emerging Writers Festival – increasingly enlist the skills of Auslan interpreters.

But we’re still moving too slowly. In 2015, we have the technological means to offer greater accessibility to the deaf and hearing-impaired community than ever before. We have no excuse. In the US, Netflix worked with the National Association of the Deaf to ensure 100% of its programming was captioned by the end of 2014. So far, most Australian television networks display no such commitment to accessibility. More onus needs to be placed with them. Meeting basic standards – i.e. merely having captions – doesn’t cut it. Networks must be prepared to invest in providing a high-quality service; to show that they value deaf and hearing-impaired viewers. Lip service is not enough.

Image: Daniel Oines / flickr